“Aging for most of us,” Lee Gutkind writes, “is a silent process, of which we are often unaware—until a transition, an awakening, occurs.”

For Gutkind (CGS ’68), an accomplished author of nonfiction, that awakening first occurred on his 40th birthday, when an interrupted meal in a decaying Pittsburgh restaurant made him feel closer to “old” than he had thought. But it wasn’t until his 70th birthday that a series of personal blows left him unmoored and unsure how to move forward. So, he did what he hadn’t done before, delving into his past and present in an attempt to illuminate his remaining future.

For Gutkind (CGS ’68), an accomplished author of nonfiction, that awakening first occurred on his 40th birthday, when an interrupted meal in a decaying Pittsburgh restaurant made him feel closer to “old” than he had thought. But it wasn’t until his 70th birthday that a series of personal blows left him unmoored and unsure how to move forward. So, he did what he hadn’t done before, delving into his past and present in an attempt to illuminate his remaining future.

Gutkind has made a career immersing himself in the lives of others—people like baseball umpires, transplant surgeons and veterinarians. Once described by Vanity Fair as “the Godfather behind creative nonfiction,” his work focuses on telling factual, highly reported stories with the kind of literary flair usually seen in novels. The founder of Creative Nonfiction magazine and a Pitt emeritus professor, he even helped build a graduate program in the genre in Pitt’s Department of English.

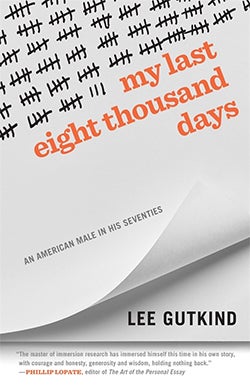

Now—after writing or editing more than 30 books—his newest work is his most personal, by far. “My Last Eight Thousand Days: An American Male in His Seventies,” (University of Georgia Press) is an exploration of self that writer Gay Talese describes as “A must-read for all of us longing to peel back the truth of ourselves.”

Pitt Magazine talked to Gutkind about aging, memoir and what a “true story” still means in today’s cultural climate.

Pitt Magazine: Why do you think we associate the word loss with aging?

Lee Gutkind: People assume you’re fading away from the things you do; I can’t tell you how often [I’m] asked when will or if [I’m] already retired. We are old but we are also capable, and incredibly strong, and have a lot to give to the world. I know that, if the statistics are right, I may have less than 8,000 days to live, but I, many of us, intend to make those 8,000-or-less days even more productive than our first 25,000 days.

PM: When did you start writing this book?

LG: It was probably in my mid-to-late 60s. I would write a little bit, take notes, and deal with other writing projects. When I hit my late 60s, I decided to commit to it.

PM: What made you commit to it then?

LG: I had always been this charged, super productive writer-teacher-editor and continued to work really hard. But the year I turned 70, some of the [relationships] that I had relied upon fell apart: my two best friends died; my mom died. What really killed me was the falling apart of this book project that I thought was going to be the literary triumph of my life. I really didn’t know what to do. I certainly didn’t feel like committing to another immersion, so it was then time to change my life and writing—do something I had never before done.

PM: In that sense, how was immersing yourself in yourself different?

LG: This was a big change for me. I had to step back with my personal camera, the lens in my mind’s eye, and start to look into myself, almost as if I was someone else, and try to decide certain things about my life that I had only confronted from time to time with a psychiatrist.

This kind of work, writing a memoir, is like being with a shrink in many ways. It’s the same way in the writing process. That’s what makes it exciting [as well as] arduous to do. You write something, and the writing triggers another memory. Or, as you write and re-read what you have written, you realize very often that the things you are typing, thinking and feeling may lead to deeper memories, conflicting conclusions and surprising revelations.

PM: So, how did you juggle all those memories?

LG: Some [memories] of course, came back easily because there are certain things in life that we can never forget. Like the day I stood watching my father’s shoe store burn down. I can still smell the ashes and the burning rubber from the tennis shoes. My father and I were in constant conflict, but the impact of his loss, eventually, in some way, brought us back together. If I were to write this book again, which I won’t, there would be so much more [because] I dug so deeply into my past.

But memoirists need to look really carefully into what they say, especially the things that can be fact-checked, and make sure that what they’re saying about the times, places and people are as true and accurate as possible. In a memoir, the whole story has to be credible. If the reader trips over something that they know is wrong, then your credibility as a narrator can be threatened.

PM: As someone who has immersed himself in writing fact for decades, what has it been like to see this climate evolve into this time of people questioning what fact even is anymore?

LG: I’m worried about what’s going to happen next not just because of the possibility that people make stuff up or that facts are no longer literally taken. But it concerns me also that [in] the journalistic community especially, reporters are being so subjective; it’s very difficult to be able to trust what you read anymore. What’s going to be a real challenge for us from now on is: How do we determine or define “fact”?

PM: One of the things you grapple with throughout your book is what you call your public persona. Could you describe what you mean by that exactly?

LG: We are different people in public than who we really are with our most trusted friends or by ourselves. Early in my life, when I came back from the military, I realized I didn’t want to be the person [I had been] anymore. So, I began to craft in every way possible the way I wanted people to conceive of me in public. This didn’t necessarily mean I changed because often when no one is around to judge you, you may well revert back and become the person that you were. I made a point in my book about how losing so much weight changed me in so many different ways, but every time I came back to my house and looked in my bathroom mirror, I may have lost 60 pounds, but I could not escape the shadow of myself at 225.

PM: And so how did turning 70 affect your public persona?

LG: In the book, I write about how hard I worked to keep [my public persona] intact. As I got older, I had to work increasingly hard to show the world who I wanted them to see.

PM: Were these things that you had actively thought about throughout your life or was this, as you started writing this book, you sort of just started picking up on?

LG: I’m not sure how hard I actively thought about it, although it was certainly something I worked hard at from the beginning. And fitting in to a conservative English department, with no advanced degree whatsoever and no real credibility as an academic, I had to really work hard to think about who I was and how I wanted to present myself to my colleagues who were so very different than I was. That was a struggle.

PM: Did you feel like you did in the end?

LG: Yeah; in many ways, I feel like a college professor now [and] continue to teach at a different university. But I’ve been so incredibly fortunate that the University of Pittsburgh gave me not only an education with some terrific faculty mentors, but also the opportunity to be part of an academic unit where I in no way, academically, belonged. They took a chance by valuing and validating my personal experience as a writer. It one of the biggest breaks of my life.

PM: What would you like to fill those last 8,000 or so days with?

LG: Well, I’m working on another book, and I will continue to write and teach and edit and use what I have learned as a person who has lived 77 years to help and encourage others to remain vital and strong.

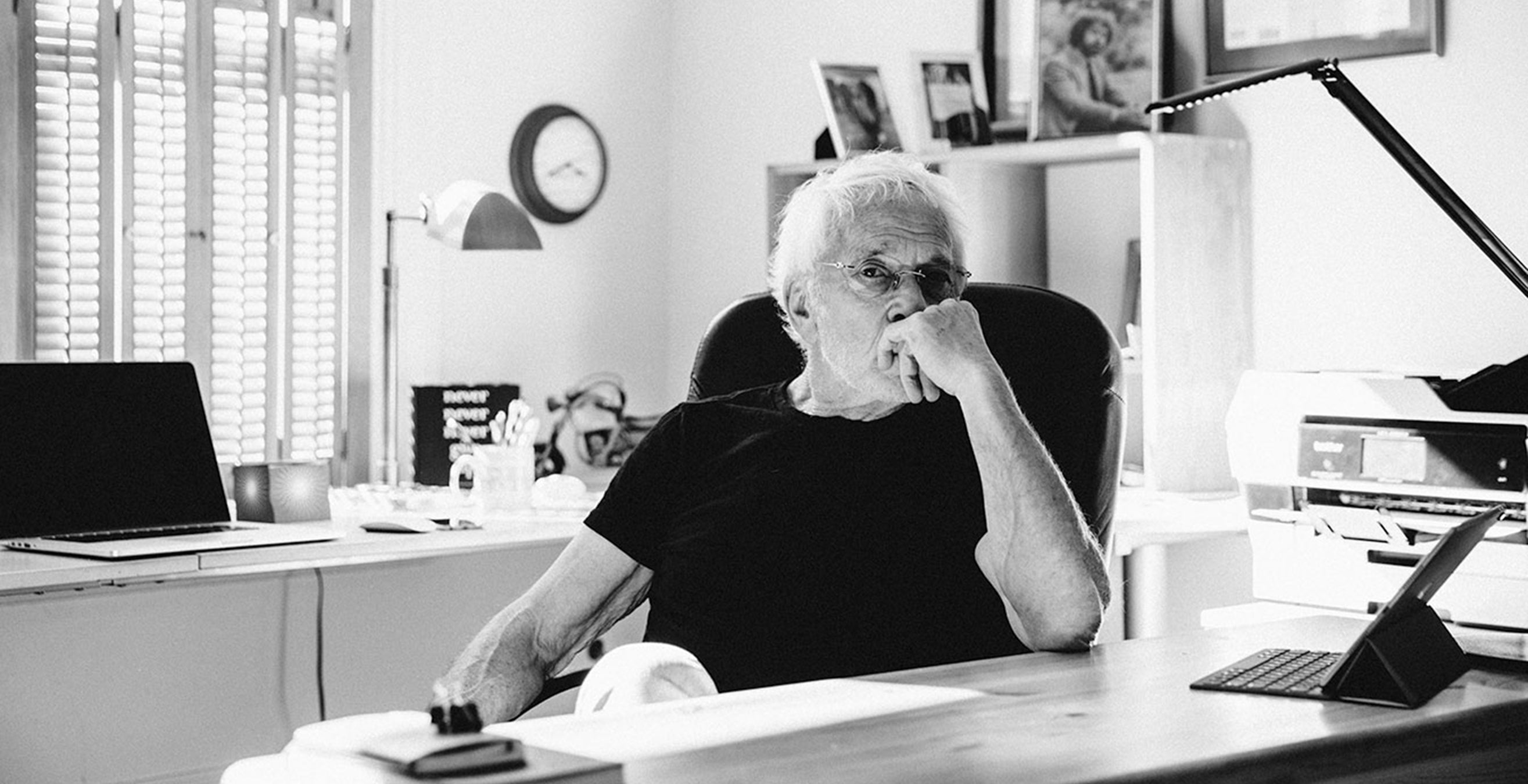

Cover image: Lee Gutkind