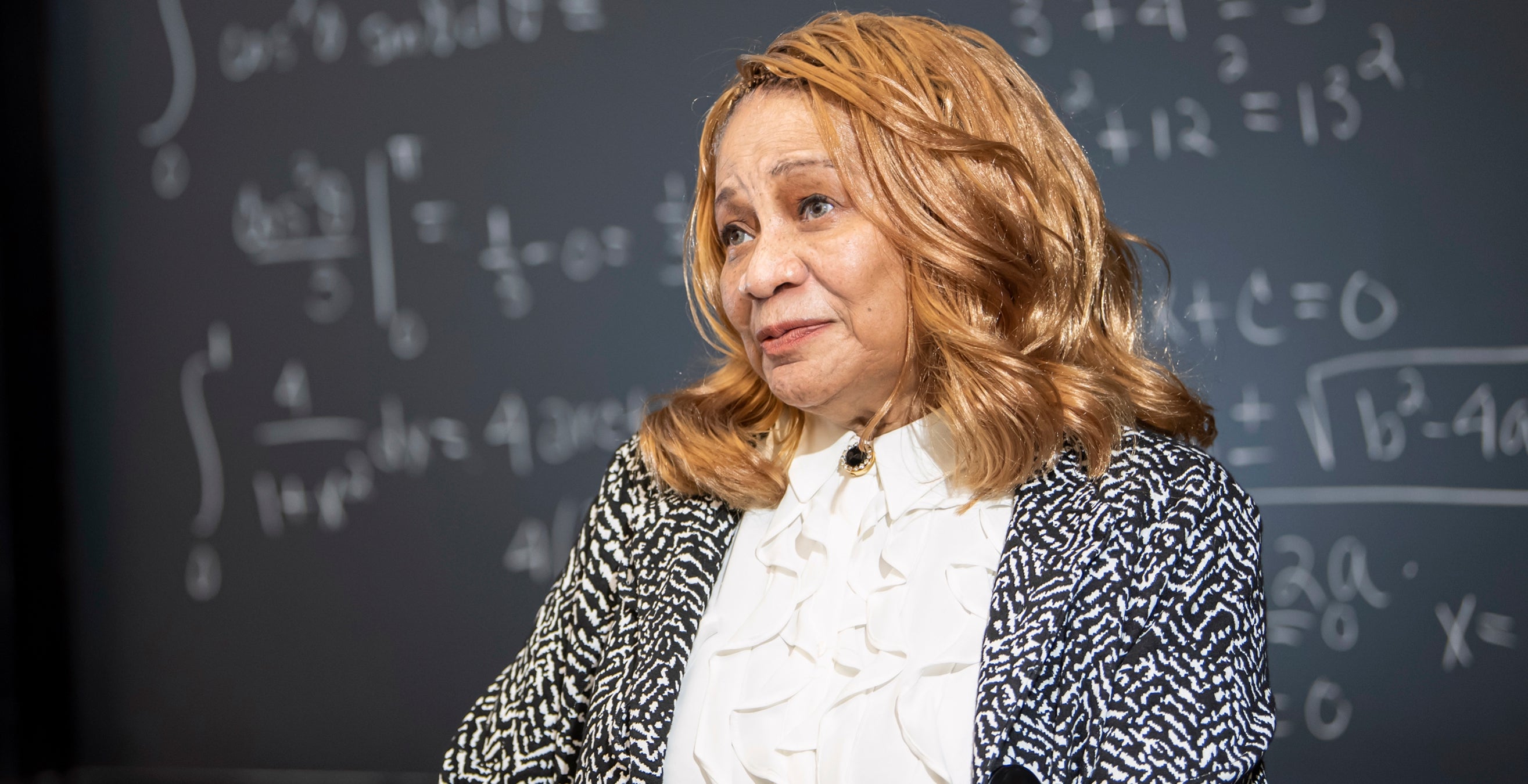

Elayne Arrington has come to the theater to watch a new release—a movie she’s never seen before, a story she’s never heard. And yet, as the plot unfolds across the flickering screen, it begins to feel painfully familiar.

The movie is “Hidden Figures,” the motion picture based on the lives of three female African American mathematicians at NASA in the early 1960s—a time when blatant segregation was still a part of everyday life.

Arrington, her eyes glued to the big screen, watches what Katherine Johnson must do when she needs to go to the bathroom while at work. Rather than use the restroom down the hall, she must run nearly a half-mile from her NASA office to the “colored bathroom” in another building. Arrington wipes away a tear. She can relate.

By movie’s end, Johnson—despite enduring racism and sexism—deciphers the flight pattern that enables John Glenn to be the first American to orbit Earth. Again, Arrington wells up.

As the credits roll, she and the other moviegoers are giving a standing ovation. Arrington’s applause is about more than just appreciation of what the “Hidden Figures” women accomplished, however. For her, the movie captures much of her own journey as a Black woman excelling in math and science.

She, too, had been a gifted mathematician who encountered prejudice in high school and then as the first African American woman to graduate from what is now called the University of Pittsburgh’s Swanson School of Engineering. Like Johnson, she worked in the aerospace industry. She tracked the flight patterns of Soviet planes at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio.

“It was surreal watching the movie,” Arrington recalls. “Someone actually got what went on and how I felt.”

It wasn’t until “Hidden Figures,” released in 2016, that she even knew the stories of Johnson and her colleagues, Dorothy Vaughan and Mary Jackson. “If I had known they existed, it would have been such a comfort,” says Arrington, as the three women would have been inspiring role models to her, just by being trailblazers in math and science, much like Arrington would become years later.

But better late than never. Vaughan and Jackson had already passed away when the movie was made; but Johnson, born in 1918, was still going strong. Arrington, hoping to meet her, secures the email of Johnson’s attorney and starts drafting a note:

“As the first African American female graduate of the University of Pittsburgh School of Engineering in 1961, I did not have a role model,” she writes in part. “I understand that requests are not few, and her contacts must be very limited. If there is a way that a meeting can be arranged or a sighting, I am very interested. … Knowing of her has been an inspiration to me.”

Arrington checks and double-checks her wording to ensure the note will achieve a response.

Arrington’s life has always been about achieving results. In 1946, as a six-year-old second-grader, she boasted to her father she could do long division. To test her, he jotted 1296÷36 on a piece of paper and asked the answer. The youngster stared at the problem incredulously. She hadn’t tried numbers that big before. But she worked at it until she had the answer: 36.

“You are smart!” exclaimed her proud dad, Henry, a steelworker and retired World War II second lieutenant. “If you keep at it,” he added, “you can go to college.” He had wanted to go to college, too, but it was then an unreachable dream.

Arrington grew up in West Mifflin, a steel town in the then-polluted shadow of Pittsburgh. She was intensely smart, but she still had other teenage dreams. In junior high, she really wanted to be a cheerleader: “I could do a split, but another African American girl could do a flip,” she remembers. “There could only be one African American cheerleader, and I couldn’t do a flip, so that was that.”

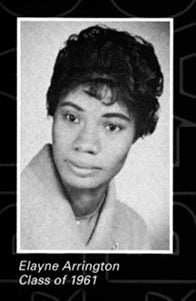

But she could do academic flips. She prided herself in solving math problems that stumped her classmates, sometimes spending late nights at the kitchen table calculating answers. She got straight A’s at Homestead Senior High School and, as the best student in her class, she was sure she was destined to be class valedictorian come senior year.

Yet, she says, the school suddenly deviated from the norm and named the class president, a white male student, as the valedictorian.

Upset, she took solace in receiving a scholarship to attend Pitt. She remembers that the recruiter was gruff when they first met, but as soon as he looked at her academic record, his tone changed. Her 797 out of 800 math SAT score reinforced her flawless grades. Her academic prowess resulted in a full ride—academic, with room and board—via a scholarship cosponsored by a Pittsburgh machinery company.

But then it happened again. A few weeks after learning she was awarded the scholarship, she received a follow-up letter—it was being rescinded. The letter explained that the machinery company’s leadership wanted to hire the recipient after graduation, but they believed that women never made it through engineering school. They awarded the scholarship to a man instead.

But then it happened again. A few weeks after learning she was awarded the scholarship, she received a follow-up letter—it was being rescinded. The letter explained that the machinery company’s leadership wanted to hire the recipient after graduation, but they believed that women never made it through engineering school. They awarded the scholarship to a man instead.

The heartbreaking decision was evidence of a national shortcoming: Women at that time made up only about 1% of all engineers in the workforce, regardless of their ethnicity; and, according to the National Science Board and U.S. Department of Education, there were fewer than 20,000 women each year earning undergraduate degrees in the science and engineering disciplines. (In 2018, in contrast, there were more than 464,000.)

Officials at Pitt were apologetic for the change, says Arrington. Through the University and the Society of Women Engineers, she still received a full-tuition scholarship, but she would now have to commute to and from school nearly an hour each way.

The one advantage to coming home every night was seeing friendly faces. At Pitt, she was the only woman—let alone Black woman—in her class. In fact, she knew of only two other women in the entire engineering school.

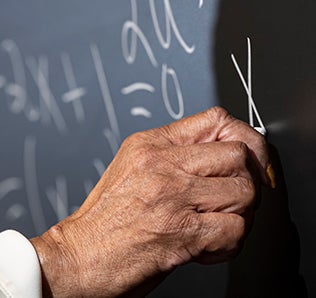

Her engineering drawing class was a sampling of what she faced. She remembers that the professor told her: “Girls always come up here, but they never finish, and you won’t finish either.” Then he glanced at her hands and added: “Besides, you’re never going to be able to draw with those fingernails.”

But it wasn’t her long nails that were a hindrance. In high school, she had to take home economics, instead of drafting like the boys, so she had no experience doing that type of drawing. But Arrington remained undaunted: “I just practiced and practiced, and finally I could draw a clean, straight line.”

Week after week, she dragged her unwieldy drafting board on the bus and up the hill to Old Engineering Hall. On one particular day, the commute caused her to arrive late for a class where the professor had assigned a particularly difficult question for the day’s lesson. None of her classmates shared with her that, because of time constraints, the professor told them to complete only half of the drawing.

When she turned in the finished assignment based on analytical geometry, the professor was taken aback, asking what prompted her to do the full drawing. Only then did Arrington realize that she’d done double the work. But, she recalls, the professor never doubted her again.

As he and other professors began to accept her, however, she remembers that most of her white male classmates stayed aloof. In essence, Arrington had two glass ceilings to break through—gender inequality and racism—and she wasn’t sure what was behind any given snub.

“Some of it may have been racial prejudice,” she says, “but they didn’t even have to get to racial because being a girl in engineering, being female, was enough.”

After she earned her undergraduate degree in 1961, she got a position as an aeronautical engineer at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base. She remembers that the man who hired her was Latino, which likely made him more open-minded to hiring her, another minority.

After she earned her undergraduate degree in 1961, she got a position as an aeronautical engineer at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base. She remembers that the man who hired her was Latino, which likely made him more open-minded to hiring her, another minority.

Her job made her a participant, like Johnson, in the space race. While Johnson deduced flight patterns for American astronauts, Arrington used the same math skills, only in reverse, analyzing Soviet aircraft reconnaissance data, which helped reveal why, at the time, Soviet rockets were outperforming their U.S. counterparts.

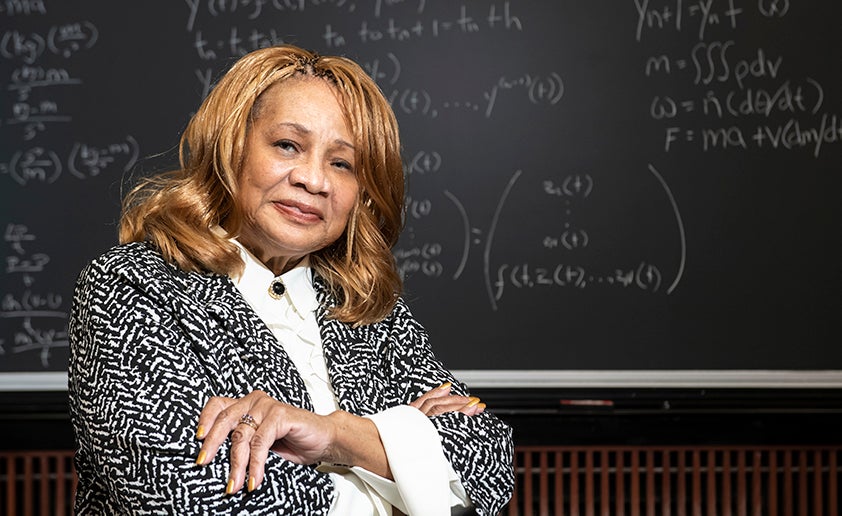

During her career as an aeronautical engineer, math continued to be her passion, and she pursued advanced degrees.

“There’s always been magic in complex math calculations,” she says. “I used to think about problems all day long. Sometimes I solved the problems in my sleep. But then I would wake up and couldn’t think of what I did. So I trained myself to write down the solution immediately.”

She earned a master’s degree at the University of Dayton in 1968, then a PhD in 1974 at the University of Cincinnati, becoming the 17th African American woman in the country to earn a doctorate in mathematics.

With her graduate degrees, she soon decided to return to academia full-time to teach and perform research in finite group theory, a component of abstract algebra. Given her elite status, she had offers from multiple schools. She chose Pitt: “My mother, Ida, always talked about Pitt. That was the only school.”

Upon returning to campus as an assistant professor in 1974, she found a more welcoming environment, but it wasn’t perfect. Not long into her tenure, she recalls, she stepped into an elevator in the Chevron Science Center on a warm summer day. Several male professors, dressed in shorts and sandals, were also on the elevator, but they were oblivious to her until one of them spilled a drink.

“I’ll have to call the janitor,” she remembers someone saying as he stepped off the elevator. Then, he looked at Arrington. “Oh, the maid is here,” he quipped, even though she was dressed in office attire.

“You look more like the janitor than I look like the maid,” Arrington shot back.

Dealing with such rudeness, stereotyping, even blatant racism wasn’t an everyday occurrence, but Arrington says it wasn’t rare, either. The ostracism pushed her toward building camaraderie with other women in the math department, especially faculty member Beverly Michael, when they were the only two.

Angela Athanas, a lecturer at Pitt, bonded with Arrington, first as a graduate student of hers in the 1980s, then as her research assistant and eventually as her colleague.

“She was great, a very detailed teacher,” says Athanas. “She was always so classy, very elegant with a scarf and a jacket. She was so professional but also compassionate.” Athanas says she will always remember that after her mother died, Arrington sent her cards and other remembrances on Mother’s Day.

Arrington has witnessed a very different college experience for minority students than what she remembers from her undergraduate years: “I know the marginalizing experience I had over 60 years ago couldn’t happen at Pitt today. There are now local chapters of the Society of Women Engineers and the National Society of Black Engineers. Dr. Sylvanus Wosu and Dr. Alaine Allen in the diversity office of the Swanson School of Engineering do a magnificent job.”

And the Swanson School continues to make strides toward becoming a more equitable space for all.

“As COVID-19 has shown us, we need people like Elayne who can solve complex problems to benefit society,” says U.S. Steel Dean of the Swanson School of Engineering James Martin II. “By 2050, the demographic shift in the U.S. will be majority minority, and so the STEM fields need to develop the workforce of the future if we are to maintain economic prosperity for all. This requires us to broaden opportunities now for underrepresented minorities in engineering if we are to realize a potential $8 trillion economic impact. What Elayne had to fight against in order to succeed needs to inform how we develop a better path for future engineering students.”

“Ultimately,” he adds, “if we are to maximize human potential, having a safe, welcoming environment is absolutely vital for knowledge generation and for learning. I’m certainly committed to making sure that the Swanson School and the University of Pittsburgh are the best places for individuals to come and do their best work.”

In 2012, at age 72, Arrington scaled back to working part-time, ultimately retiring in 2018.

But she has not retired from learning. Five years ago, she took a class in New Testament Greek at the Pittsburgh Theological Seminary so she could read the Bible in its original language. It was demanding. But just like when she stayed up late into the night solving math problems, the challenge of learning was appealing, which is why today, at 80, she’s on track to earn her master’s degree in theological study next spring.

Nothing keeps her from her class—not even a hospital stay for back surgery last December. One of her two daughters, Karyn Elayne Taylor, reports her mother would dutifully go online to take her class from her hospital bed. No one was allowed to disturb her, says Taylor: “Not even the doctor. Her door was closed.”

While recuperating at home from the surgery last February, Arrington learned that Katherine Johnson had died.

She was saddened by the news. The two never did meet, and she never did get a response from Johnson’s attorney. Later, to her shock, she found the persuasively written note sitting in her email draft folder. She had accidentally neglected to hit send.

“I really wanted to meet her,” she says wistfully. Johnson is, to her, a testament that so much is possible for African American women, despite being saddled with unfair restraints.

“I really wanted to meet her,” she says wistfully. Johnson is, to her, a testament that so much is possible for African American women, despite being saddled with unfair restraints.

But, of course, Arrington is herself an inspiration to countless women at Pitt and beyond.

Wanda Austin, another Pitt alumna, knows well the power that comes when a Black woman believes she can overcome injustice. Austin—who earned a master’s degree in systems engineering and mathematics in 1977— was president and CEO of The Aerospace Corporation from 2008 to 2016. The nonprofit is a leading architect for the nation’s national security space programs.

Like Arrington before her, when Austin was earning her degrees at Pitt in the mid-1970s, she was often the only African American and woman in her classes. “It was isolating,” she recalls. That’s why Austin would visit Arrington during office hours.

“She reaffirmed to me that I could do it. She was proof positive that I could do it. She was always a shining light for me,” says Austin, who is internationally recognized for her work in satellite and payload system acquisition, systems engineering, and system simulation.

Austin returned to Pitt in 2017 to be honored by the Swanson School of Engineering. Arrington had been honored herself a few days before, and when she heard that the school was going to celebrate a retired aerospace executive, she stopped by the banquet. She had no idea that the honoree was Austin. Arrington was seated with the guest of honor—and the one-time student and professor recognized each other right away.

Austin, beaming at Arrington, confided: “You were my role model.”

No email needed.

This article appears in the Fall 2020 edition of Pitt Magazine.