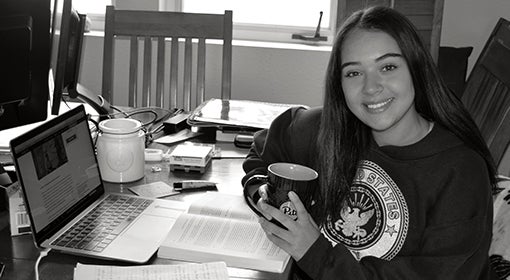

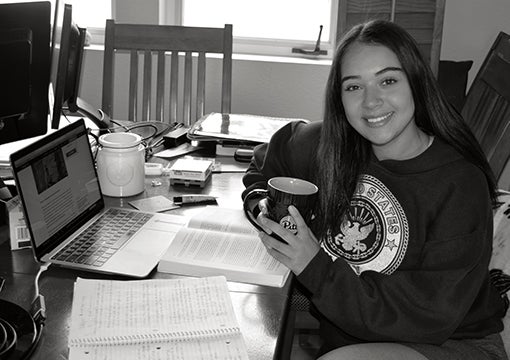

It’s 5 a.m. and pitch-black outside when Maya Stieben’s alarm goes off. Five minutes later, still groggy, she drags herself from bed. She brushes her teeth, applies her makeup and puts on her sweatshirt and leggings.

Off she goes for her morning cup of coffee before heading to her Aspects of Sociolinguistics class.

She doesn’t have to go far. She slides out of her bedroom in her family’s home in Tacoma, Washington, tiptoeing through the darkness to not awaken anyone, and ends up in the kitchen, where she gets her caffeine fix.

Mug in hand, she settles into her corner of the dining room table, where her laptop sits surrounded by notepads, books and pens. About a half-hour has passed since her alarm jolted her from sleep. The sun still isn’t up as she begins to read, getting her brain working so she won’t be a “zombie” when she logs into class.

Stieben began her studies—learning how language and social relationships influence each other—earlier in the semester on the University’s Pittsburgh campus. But now she’s home, some 2,500 miles from the Cathedral of Learning, which explains why she’s up before dawn. The class begins at 9:30 a.m. Eastern Daylight Time, which is 6:30 a.m. in Tacoma.

Blame the early wake-up call on COVID-19. The pandemic forced Pitt to make an extraordinary pivot from traditional on-site learning to remote instruction, which meant that the 2020 spring semester would have to be completed virtually and at a distance.

Blame the early wake-up call on COVID-19. The pandemic forced Pitt to make an extraordinary pivot from traditional on-site learning to remote instruction, which meant that the 2020 spring semester would have to be completed virtually and at a distance.

Pitt had plenty of company in its semester’s abrupt derailment. The challenge facing universities nationwide is unprecedented. First and foremost, everyone—from Stieben to Pitt Chancellor Patrick Gallagher—is focused on the health and safety of their families and communities.

Then, of course, there are the financial and way-of-life repercussions. It’s been widely reported that lost revenue for institutions of higher education will be in the billions of dollars. As for Pitt, “The University is facing one of its largest potential financial shocks in its history,” says Gallagher. At the time this article was written, it was estimated that there are nearly $20 million in losses just from pro-rated refunds of fees for room and board after students were asked not to return from spring break.

As for students like Stieben, sacrifices are everywhere—from annoyances like having to wake up at the crack of dawn, to greater concerns, such as job losses and financial and health hardships.

Staff and faculty members have a host of challenges, too, such as dealing with a lack of childcare options while they work from home or teach online, or having spouses furloughed from jobs, or making room for adult children to move back home to avoid COVID-19 hot spots.

The list of concerns for everyone could go on. And on.

But so could the list of ways the University community is responding proactively, creatively and compassionately to the new and difficult circumstances the pandemic presents. Researchers are zeroing in on vaccine and treatment possibilities; alumni are digitally converging to offer mentoring and financial support to current students; technological assistance is being provided to local school children learning from home; the University’s senior leaders are donating portions of their salaries to student aid. And on and on.

Perhaps nowhere are Pitt’s resilience and resourcefulness on clearer display, however, than in the students and faculty who continued to excel while moving with a changing tide.

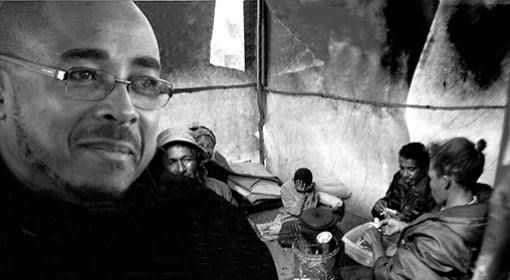

For instructors like Pitt’s Abdesalam Soudi, there is one constant, despite the move to virtual classrooms and regardless of the scenario—continuing to teach students without compromising academic integrity. So, at 6:30 a.m. Pacific Daylight Time every Tuesday and Thursday for the rest of the spring semester, Stieben and her 23 classmates in the Aspects of Sociolinguistics class are greeted online by Soudi with an image of the Oakland streets imposed in the background.

Stieben is ready to learn. “No one wants to get up at 5 a.m.,” says the linguistics major, who plans to graduate in spring 2021. “But I want to be in class. I look forward to the discussions and learning with my teammates. It is a unique learning environment, but Professor Soudi makes it worth my time.”

In the scramble to get ready for remote teaching, hundreds of Pitt faculty, like Soudi, ramped up their technology intelligence and oriented themselves to new platforms to “ignite learning,” says Tinukwa Boulder, borrowing part of a mission statement from Pitt’s School of Education, where she’s director of innovative technologies and online learning. But she’s been most impressed with what she’s observed as the faculty’s “emotional intelligence.”

“I’ve seen a real response in them being flexible with deadlines, rethinking assignments, being mindful of the well-being of their students, because some of them have lost jobs, are caring for parents and have other worries beyond just the regular day-to-day,” she notes.

Boulder, who grew up and studied in England, came to Pitt in February to help the School of Education develop online teaching resources. Then, the pandemic hit. Ever since, she’s been engulfed in nonstop strategies to help students and faculty access the technology. She’s heartened by simple but engaging techniques that professors are creating, such as Soudi connecting students to their college home through the Pitt campus backdrop on his Zoom class.

Zoom, of course, has become the pandemic’s go-to online platform for teleconferencing—used for virtual education, business and even family get-togethers. It presents a computer screen with a tic-tac-toe board of people’s faces in real time, with up to 100 interactive participants. All can talk to each other.

Early in the spring semester, Zoom was not a teaching tool for Soudi, but that changed in mid-March when COVID-19 left universities like Pitt with no choice but to reduce campus operations as much as possible. The faculty was tasked with transitioning to remote learning. In preparation, Soudi immediately sent his students an email to assure them that learning would continue via Zoom. Some students stayed in touch by calling his cellphone. In addition, he inquired about their technical needs, living situations and thoughts on how they wanted class to continue.

“I sympathized with them,” says Soudi (A&S ’13G), a Pitt alum who’s been on the faculty since 2013. “I knew there would be no coffee shops to gather in, no library to visit. I knew it would be lonely.”

“I sympathized with them,” says Soudi (A&S ’13G), a Pitt alum who’s been on the faculty since 2013. “I knew there would be no coffee shops to gather in, no library to visit. I knew it would be lonely.”

Recognizing this, he synchronized the online learning with the 9:30 a.m. class time. “I wanted to keep the learning community together,” he explains. He ensured that the guest lecturers already scheduled to visit his classes would still make appearances—just over the internet—such as a researcher from the Department of Surgery who Zoom chatted with students about nonverbal communications in the operating room, or an intensivist who talked about patient-centered decision-making in the ICU.

Soudi also created in-class writing time and shortened his lectures to ensure that his pupils could give him their undivided attention, despite the strange atmosphere of a video feed. And because the students couldn’t do field work—going beyond the classroom to examine language variations across ethnicity, race, identity and settings—Soudi devised methodology exercises where the students could design a study and analysis, as if they were in the field. Stieben says all of the adjustments to the suddenly virtual course were met with enthusiasm and appreciation by her and her classmates.

The students’ satisfaction is especially meaningful to Soudi, who, in 2017, was awarded a Diversity in the Curriculum Award from the Office of the Provost. He says he found that one of the biggest challenges to remote learning is creating inclusive classes. “Professors are trained to teach in person. When it’s remote, we need to figure out how to keep it student centered.” The Zoom format is helpful, he says, as he can look at the students, monitor hand waving, and set up classroom teams and chat sessions to facilitate participation.

There are benefits to online learning, adds Boulder. It offers flexibility, students can learn at their own pace, and it reduces issues of time and space. As the country’s educational sphere considers the divide between who has access to technology and issues of equity, she believes learning remotely will advance, as it’s a way to bring a new dimension to how more people can access the learning environment.

In these unusual times, Pitt is also trying to keep campus life thriving virtually through a new site called Pittwire Live. Stieben, Soudi and every other Pitt student, faculty member, employee and friend can join together virtually in activities and attractions, everything from cooking classes to open mic nights to lectures.

“This is a way for us to connect socially and physically and emotionally,” says Kate Ledger, Pitt’s assistant vice chancellor for marketing.

She points out that, like virtual classrooms, this is uncharted territory for the University: “Before we closed campus, we had a lot of events happening on a daily basis on campus, but we did not host a lot of virtual events, and it’s amazing the speed with which our community responded to post events virtually.”

Like Ledger, Kathy Humphrey, Pitt’s senior vice chancellor for engagement, marveled at the University community’s ingenuity and desire to stay connected. “We got the site up in two weeks! Our faculty and staff and students have submitted hundreds, literally hundreds, of programs that we can use to bring the community together.”

The plan is for the new portal to become a permanent Pitt fixture. “One of the positive things that has come out of the pandemic: it has given us a new way to communicate,” says Humphrey. “It has broken down barriers so quickly, and making connections is at the essence of what a university community is all about. We can meet with each other, through Pittwire Live, in spite of our current circumstances.”

Gallagher applauds this kind of ingenuity. “The University of Pittsburgh continues to evolve during this unprecedented time. We’ve embraced remote learning and working. We’ve ramped up research related to better understanding the virus and how to stop its spread. We’ve transformed some of our residence halls into a home away from home for clinical care staff. We’ve created a volunteer network that is conducting wellness check calls on elderly neighbors in the community.”

All of those initiatives are examples of his strategy to address COVID-19. “Be flexible,” he says. “The key here is to stick to your core values and mission, be clear about what you’re trying to do and be flexible enough to adjust as we learn more.”

Stieben has certainly been flexible. So has Soudi. And so have many, many other students and professors.

Stieben has certainly been flexible. So has Soudi. And so have many, many other students and professors.

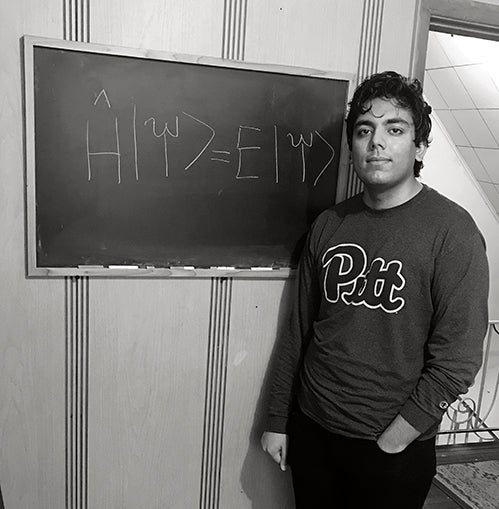

There’s Raees Khan, a senior physics major. He lives in McKeesport, Pennsylvania, where he tries to follow his normal routine. But on weekdays during the remote half of the spring semester, he has to take a different commute to class. Instead of catching two buses—a nearly two-hour trip to campus—he goes for a brisk walk in his community. He passes now silent bakeries and hair salons and the porches empty of his neighbors.

Once he arrives back home, he goes to his bedroom, which doubles as his classroom. One wall has a chalkboard, where he calculates his homework problems.

Khan’s physics professor, Gurudev Dutt, sent Khan and his other students “care packages,” each containing a microcontroller featuring programmable circuit boards and software, along with lots of wires and plugs to attach the controllers to computers.

“With the care packages,” Dutt says, “the students are able to get in learning and analysis on temperature and pressure sensors, learn programming and code using micro controls, and think about process.”

The package’s arrival surprised Khan, but he says it ended up being indispensable: “It came with instructions and everything we needed. It was a solution to allow us to finish our labs.”

The openness to learn from afar by students such as Khan and Stieben, the willingness to educate in a virtual world by professors such as Dutt and Soudi, and the preservation of campus culture by Pittwire Live makes a difference—particularly now.

“One thing that I am particularly concerned about,” says Gallagher, “is that our students—a generation of bright, engaged individuals—will miss out on the opportunities and stability that many of us have known and enjoyed. We cannot let this crisis create a lost generation. Students at the University of Pittsburgh are talented, resilient and creative, and they believe in the power of community. We need them to do the great things that they are poised to do. This means helping our students get connected in their communities, staying on track to further their careers or future studies and ensuring they are positioned to contribute and make the world a better place. Right now, especially now, they give me great hope for our future.”

Stieben says she stayed on track, for the most part, throughout the spring semester. It just meant getting up at 5 a.m. every Tuesday and Thursday.

This article appears in the Summer 2020 edition of Pitt Magazine.