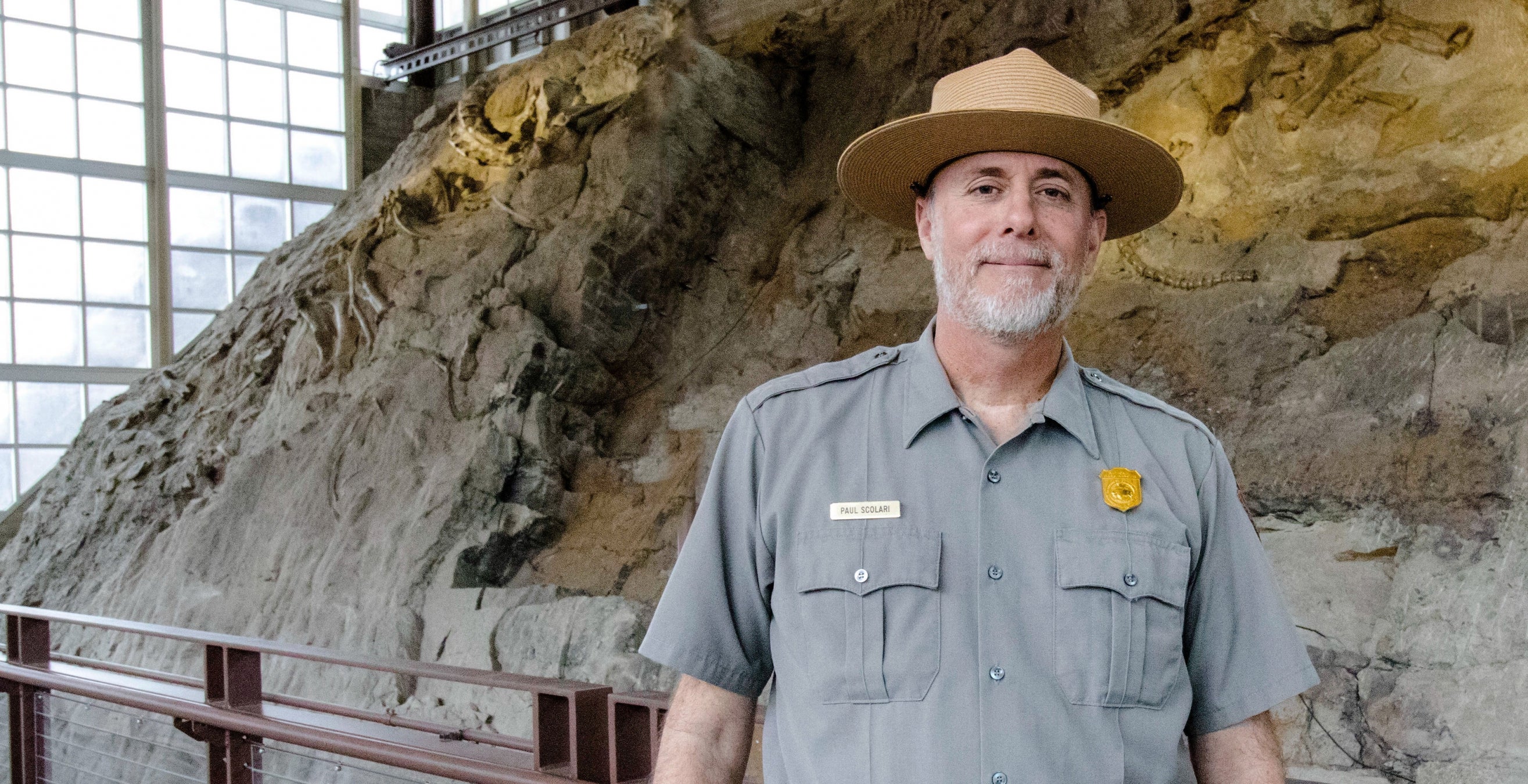

Paul Scolari is in charge of a natural treasure more than 150 million years in the making. As the superintendent of Dinosaur National Monument (DNM) in Utah and Colorado, the Pitt-trained art historian oversees one of the world’s richest Jurassic paleontology sites, where visitors can get an up-close look at hundreds of dinosaur fossils embedded in rock. The 300-square-mile park, encompassing mountains, river canyons, and arid wilderness, also holds Native American pictographs and petroglyphs painted on cliff faces at least 1,000 years ago. A longtime National Park Service employee, Scolari (A&S ’91G, ’05G) leads the team entrusted to preserve and share DNM’s natural and cultural history.

What about DNM most appeals to you?

I like national parks for the reasons most people do. My wife and I did a national park tour for our honeymoon: Glacier National Park, Yellowstone, Black Hills—I got hooked. But here, all of my interests merged: the amazing natural history, the rich Native American past, its importance in the American conservation movement. It’s an enchanting, magical place.

What do you do as the superintendent of a national monument?

As the superintendent, you’re the decision-maker in all areas. You need to learn enough about a great range of things to make informed decisions. As a generalist, I rely on the wisdom and expertise of my staff, who know their stuff. I work with hydrologists, fire experts, archaeologists, law enforcement, educators … I really like the problem-solving nature of the job.

How does an art historian forge a career in the National Park Service?

In graduate school at Pitt, I studied under Kirk Savage, who researches public monuments and public memory. From him, I learned that there’s a field called public history where you could be a historian in the public sector. The National Park Service, which manages significant public architectural and archaeological properties as well as lands, was one of the first agencies that hired historians. I thought, “Oh, maybe I could do that.” I started as a historian and have been with the Park Service since 1994.

Is it true that the site has a Pittsburgh connection?

Yes! The paleontologist who discovered the dinosaur quarry here, Earl Douglass, was working for Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Museum at the time. The museum’s director, who employed Douglass, happened to be William Jacob Holland, a former chancellor of Pitt. Douglass sent 700,000 tons of fossils from here back to the Carnegie, some of which are still on display.

What’s the value in preserving a place like DNM?

Dinosaur National Monument makes the Earth’s history palpable. It’s where paleontological and archaeological discoveries continue to be made, and it preserves natural resources that are vital for maintaining biodiversity in North America. It is one of those rare places where life on Earth—both past and present—is at your fingertips. The opportunity to work in this wonderful place with skilled, dedicated employees is just incredible.

Cover image: Paul Scolari in the Quarry Exhibit Hall at Dinosaur National Monument

This article appeared in the Fall 2019 edition of Pitt Magazine.