Sometime around 1595, Queen Elizabeth I sat for a portrait, which shows her adorned in strands of luminous pearls. European nobility coveted the pearl—a gem that has been prized since ancient times. But there’s more to the pearl’s story than what glitters in imperial wealth and status.

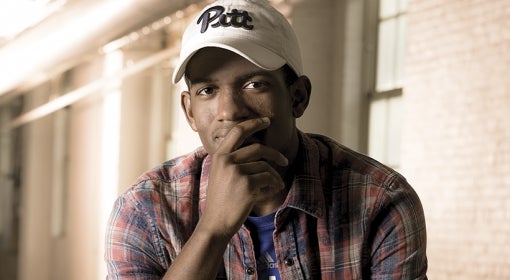

Pitt’s Molly Warsh, an assistant professor of world history, spent a lot of time during the past decade globe-trotting, digging through historical archives. She has been researching the colonial-era dynamics that surrounded the pearl industry and its Spanish-controlled Caribbean fisheries during the years following Columbus’s first voyage to the Americas.

“It’s difficult to convey the scale,” Warsh says of the 16th- and 17th-century operation. “The best estimates of marine biologists are that in the 30 boom years of these fisheries, they harvested more than a billion oysters—which produced millions and millions of pearls.”

Warsh’s research delves into the complex labor systems, economic quandaries, and range of human experiences generated by the plunder of these maritime jewels during a time of expanding colonialism. To unravel the intertwined economic, political, social, and cultural threads of the pearl industry in its heyday required Warsh to dive deep into many disciplines: economics, sociology, art history, environmental science, and others.

Because natural pearls are such a variable commodity, she explains, “it became really hard for governments to tax or regulate them in any way.” They were smuggled easily and often, and sold on black markets, where they trickled into the hands of soldiers and everyday citizens, who cherished even a single pearl not as adornment, but as a valuable bartering tool.

Spanish officials wondered how to convert this natural resource into recognizable, taxable currency. A pearl-based lexicon emerged as handlers tried to impose order and make a profit. As she combed the archives over time, Warsh began noticing new words to describe pearls based on shape, color, and size. Barrueca, for instance, eventually becomes baroque in English—a word used to describe a misshapen, irregular pearl. “Later on, this becomes a metaphor for outlandish style, for something that breaks the mold.”

Her forthcoming book American Baroque: Pearls and the Nature of Empire 1492-1700 resists the idea that the dynamics of cultivating imperial fortunes can be categorized. “The endeavor of empire is a constant struggle; it’s full of complexity,” she says. As an historian, she argues that the heart of the imperial endeavor must be viewed not only through the lens of colonial empire-builders and elites around gilded government tables, but also through examinations of the ordinary lives engaged in “small-scale, local, site-specific practices of resource cultivation,” that helped shape a political economy.

The beginnings of Warsh’s pearl project were seeded while she was a graduate student in history at Johns Hopkins University, where she earned a PhD in 2009. She then spent two years as a postdoctoral fellow at the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, based in Williamsburg, Va., where she expanded her research on global empire, focusing on British Atlantic history.

After serving on the faculty at Texas A&M, Warsh arrived at Pitt in 2012. Her thematic teaching style resonates with students, and her course on the Global History of Piracy is among the Department of History’s most popular offerings. This fall, as the interim director of Pitt’s prominent World History Center, Warsh introduced a new course on resource exploitation: how humans and their environment have interacted throughout and shaped history. It’s a course that emerged from her research on the pearl industry, from spending so much time at interdisciplinary intersections. By looking at the lives and records of these people from the past, she says, we can continue the conversation about what it means to create wealth from our environment.

History, she believes, is a conversation, a back and forth negotiation over how we ascribe value—to what and to whom—and what those implications are. Time and again, the archives remind her that “wealth is more than just money on the table. Human beings are wealth; the environment is wealth. And we have to think very hard about the relationship between those components of wealth, tradition, and value.”

Breakthroughs in the Making

Parkinson’s Discovery

Pitt researchers have uncovered a vital key to understanding why Parkinson’s disease causes degeneration of the brain’s nerve cells. A research team led by J. Timothy Greenamyre, the Love Family Professor in Pitt’s School of Medicine, found that alpha-synuclein, a brain protein related to Parkinson’s, is toxic when overproduced or mutated by cells. When this occurs, alpha-synuclein disrupts mitochondrial function, which leads to neurodegeneration. Now, the research team is developing ways to prevent alpha-synuclein toxicity, which could potentially lead to new therapies to slow or stop the progression of the neurological disease, which affects about one million people in the United States each year. Greenamyre also directs the Pittsburgh Institute for Neurodegenerative Diseases on Pitt’s campus.

How Do You Say “Bird?”

Karen Park, an assistant professor of linguistics, is using global bird migration and the study of human language to better understand aspects of biodiversity, human culture, and more. Her research is part of a £4 million project funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council of Great Britain’s Open World Research Initiative through a Creative Multilingualism grant, led by the University of Oxford. The project includes a public education component, with cross-cultural outreach to schools, museums, and community centers.

Kidney Stone Solution

A natural citrus fruit extract has been found to dissolve calcium oxalate crystals, the most common component of kidney stores according to research conducted by Pitt’s Giannis Mpourmpakis in the Swanson School of Engineering, along with colleagues at the University of Houston and Litholink Corporation. The findings, published in the journal Nature, offer the first evidence that the compound hydroxycitrate inhibits the growth of oxalate crystals and can lead to their disintegration. As part of the study, Mpourmpakis—an assistant professor of chemical and petroleum engineering—and a graduate student applied density functional theory, a computational method used to study the structure and properties of materials, to understand how chemicals interact. The discovery could eventually lead to new kidney stone treatments.

This article appeared in the Winter 2017 issue of Pitt Magazine.