Seema Lakdawala still hasn’t learned how to bake bread.

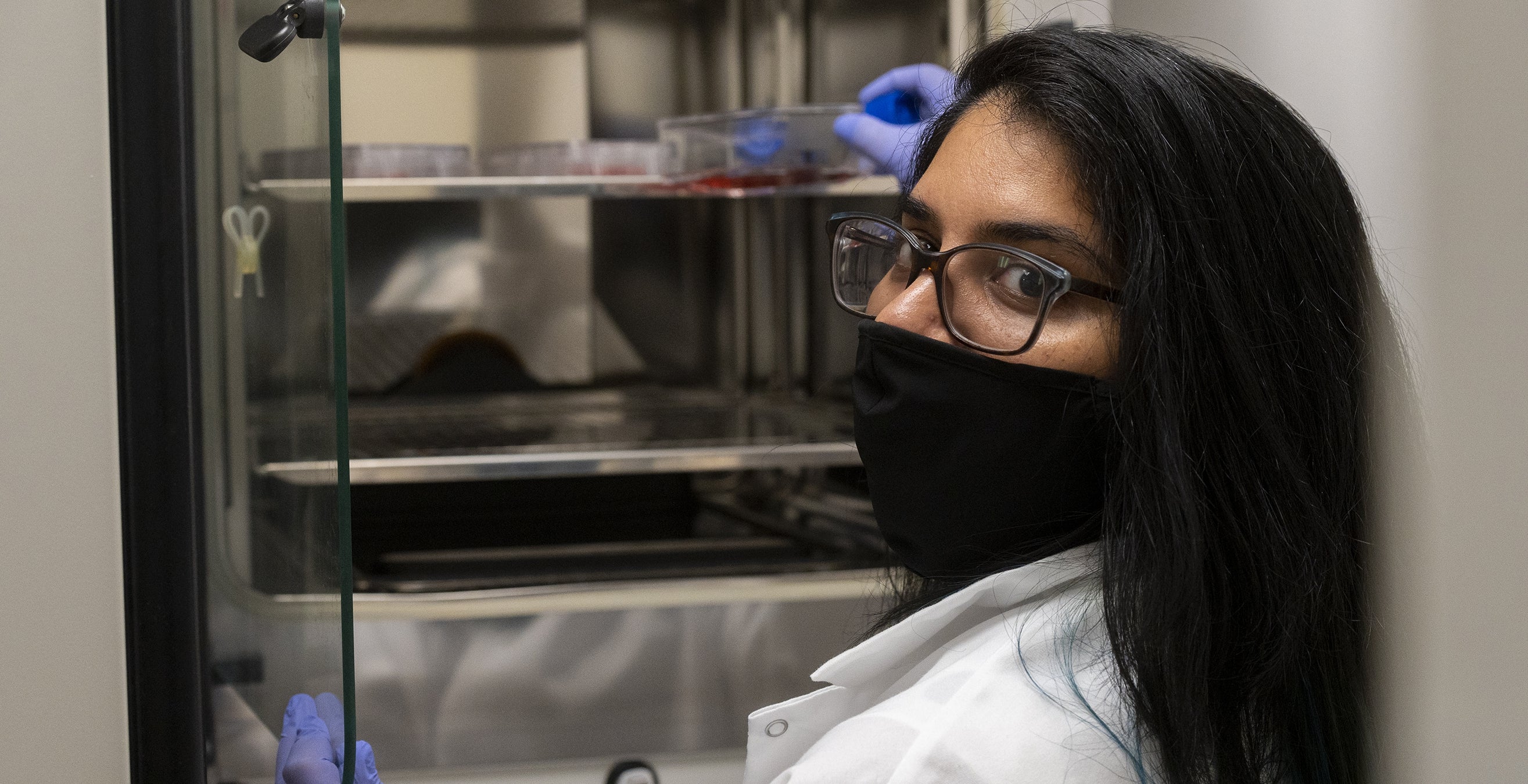

While many spent the earliest days of the COVID-19 pandemic taking up new hobbies, Lakdawala, associate professor of microbiology and molecular genetics in Pitt’s School of Medicine, found her already busy work schedule kicking into overdrive.

That’s because her research — which focuses on viruses that jump from animals to humans and how they are transmitted between people — is critical to understanding how a virus such as COVID-19 spreads.

Her work could also help us prevent, or at least prepare for, future pandemics.

Lakdawala is colead of a project aimed at identifying strains of flu that have the stability and transmissibility needed to become widespread health crises. It’s part of the University of Pennsylvania Center of Excellence for Influenza Research and Response, an initiative of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Lakdawala and the researchers in her Pitt lab are expanding on their earlier work with ferrets (whose immune response to the flu is similar to humans’) to explore factors that may influence just how susceptible an individual may be to new strains of the virus.

The team’s work will also include an investigation into the effect human mucus can have on different viral strains. Although mucus often prevents viruses from reaching cells, Lakdawala says, in some cases it can serve as a “mucus wrapper” that protects a virus so it can stay infectious in the air.

Understanding the context in which a virus emerges is particularly crucial, she explains. Lakdawala’s efforts also zero in on the role of preexisting immunity in a virus’s spread. Knowing what other viruses an individual has been exposed to could help doctors gauge how easily affected they may be by the next bug that comes along. And that, in turn, could help experts predict how widely a virus may spread.

“How much of a population fits into the susceptible category?” she asks. “Are there enough susceptible recipients for a virus to infect and spread?”

Lakdawala has been asking questions like these since 2009, when she was a postdoctoral fellow at the National Institutes of Health during the H1N1 swine flu pandemic. Her research focused on what enabled that virus to spread among humans where other pig viruses had failed.

“My goal has always been to look at what makes viruses, especially influenza, successful in human populations,” she says. “What are the properties that lead to efficient airborne transmission?”

In 2020, Lakdawala was in high demand, giving interviews to media and convening a National Academy of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine panel on how COVID-19 spread.

She teamed up with Carnegie Mellon University data scientists to launch the Public Health Interventions aGainst Human-to-Human Transmission of COVID-19 (or PHIGHT COVID), a data map tracking states’ interventions. At a time when each state was doing something different, compiling information on what was working felt like an important contribution.

“The pandemic shifted my priorities,” Lakdawala says. “My research has always had this applied part: how a virus enters cells, replicates, and so on. But during the pandemic, my lab has been doing a lot more public health policy, looking globally.”

The ultimate goal of her field is to save human life, she says, and projects such as PHIGHT COVID that help to disseminate information rapidly are critical to that effort.

“The pandemic has made me think bigger about my research program, not just focusing on animal models and cell biology but taking it to the next scale,” says Lakdawala. “What we’re building now is a program to look at pandemic emergence from basic cell biology all the way out to humans.”

This work could help scientists prevent the next pandemic before it even arrives.

Lakdawala was first drawn to studying influenza by a strong desire to have an immediate impact on health outcomes.

“Now I feel like not only can I see the immediate impact, but I have to have an immediate impact,” she says. “That’s where my vision is now and where I’m going.”

Breakthroughs in the Making

Water Works

It isn’t fantasy: The U.S. Navy has recently developed seawater-to-fuel technology on aircraft carriers, using onboard nuclear reactors to harness the carbon dioxide and hydrogen from seawater to create a liquid fuel for jet engines. Designing catalysts that can effectively take on this work, however, is difficult and expensive. Enter Pitt chemical engineer Giannis Mpourmpakis. His team, in partnership with researchers at the University of Rochester, has received a $300,000 grant from the Department of Defense to refine the process of hydrogenating carbon dioxide from seawater. Their work is expected to make the process safer, scalable and more energy efficient.

Social Rebels

Recent news about the possible harm social media can cause to teens might lead adults to wonder: How can we help them cut back? One answer: Appeal to their sense of rebellion. Research by Brian Galla, an associate professor of applied developmental psychology in the School of Education, found that high school students who are taught about the psychological hacks that social media companies use to keep people engaged were more motivated to reduce usage than those who were told about the possible long-term benefits of avoiding social media. “Teens value making their own choices, they value freedom in deciding how to think and feel and act,” says Galla. “What we’re trying to do, instead of working against that, is to harness it.”

On the Rebound

We’re all used to bad environmental news, but Pitt biologist Corinne Richards-Zawacki says there’s some good news out there, too. Her lab found signs of recovery in some frog and toad populations that decades ago were devastated by disease. The work led her and a group of colleagues to launch an institute focused on the study of ecological resiliency. RIBBiTR (Resilience Institute Bridging Biological Training and Research), which has been awarded a $12.5 million grant from the National Science Foundation, will help scientists better understand the ways nature can bounce back after being disturbed by human activity.

This story is from Pitt Magazine’s Winter ’21-’22 issue, which will be mailed in January 2022.