Her grandparents’ home was often noisy. There were grunts, groans and yelps of laughter, feet stomping, hands slapping against the kitchen counter. She would later learn that most hearing people imagine deaf households to be silent, but Katie Booth always knew better. When in the safety of their own home, her deaf grandparents felt free to use their whole bodies to communicate.

Elsewhere, and especially outside of the deaf community, that sense of freedom would evaporate.

Elsewhere, and especially outside of the deaf community, that sense of freedom would evaporate.

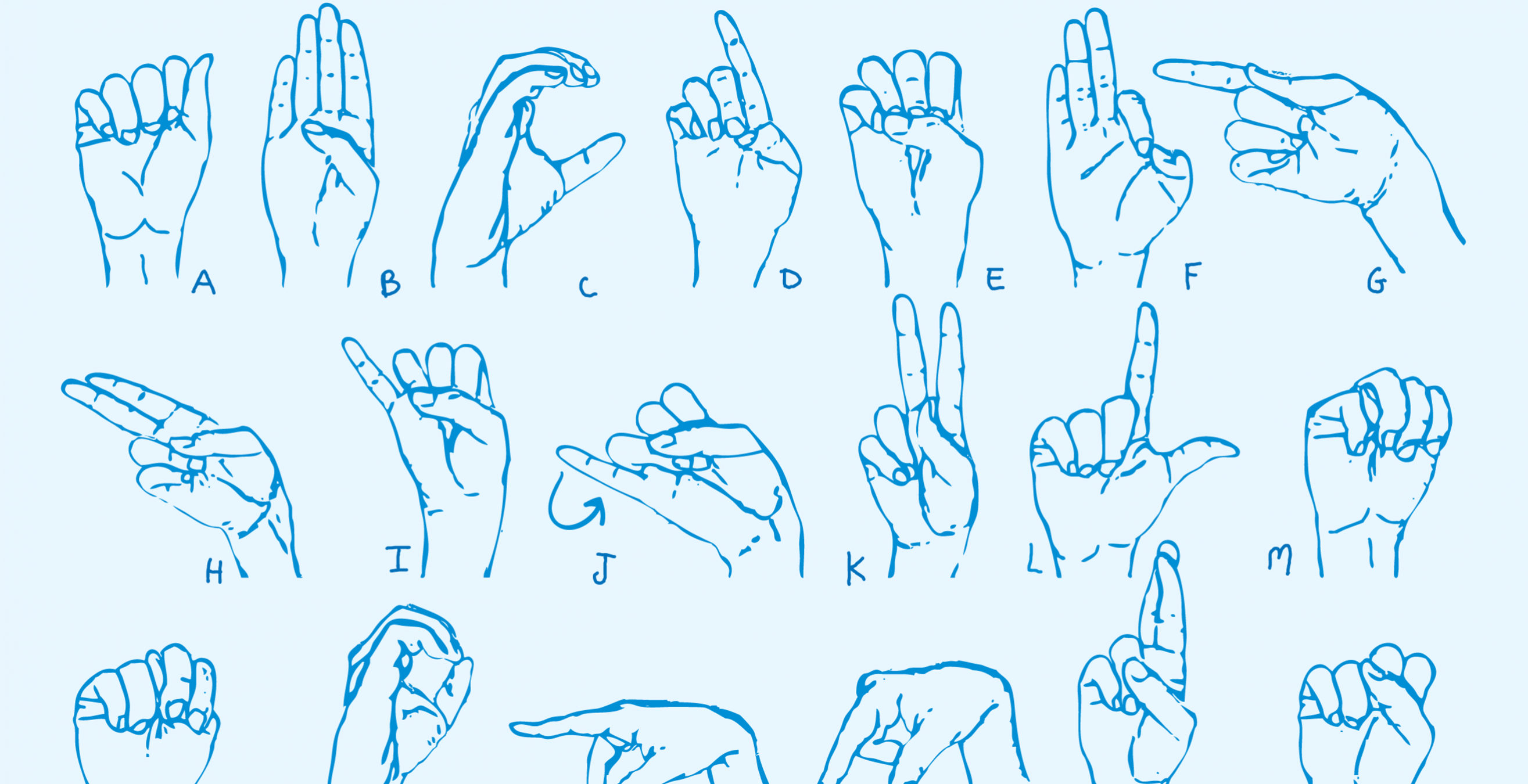

Booth’s maternal grandparents and many of her older deaf relatives were told as children that spoken English and lip reading are the ideal forms of communication, not American Sign Language (ASL). They were told not to sign and were taught instead to use their voices to speak by controlling their breath and shaping their mouths and tongues.

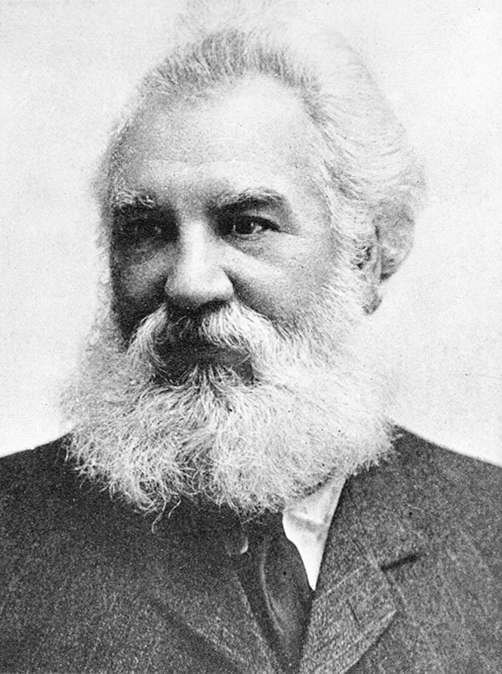

Their experience was born from oralism, an approach that was refined and heavily championed by a man more well known for his involvement in the development of the telephone: Alexander Graham Bell.

Booth (A&S ’13G), a hearing person, grew up knowing Bell to be a highly controversial figure within the deaf community. For some, like her family members, he represents shame, restriction and the false but no less painful insistence that deaf people and culture are lesser. For others, his efforts were hailed for allowing deaf people to further integrate into—and more easily communicate with—hearing society.

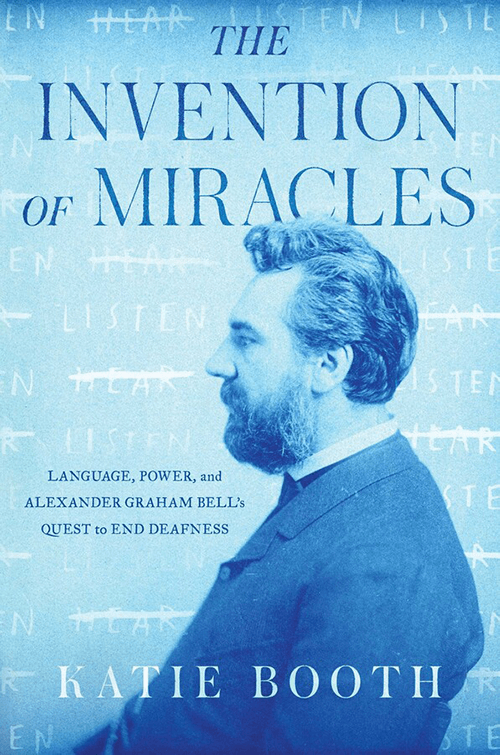

Pulling from her own family memories and 15 years of intensive research into Bell's life, Booth explores his life and legacy in her book, “The Invention of Miracles: Language, Power, and Alexander Graham Bell’s Quest to End Deafness” (Simon and Schuster). She worked extensively on the project while at Pitt, where she earned a master’s degree in creative nonfiction. After its release in April 2021, the book was named a New York Times Editors’ Choice and featured on the cover of the New York Times Review of Books, which called it “engagingly written.”

Booth sat down recently with Kenneth DeHaan (EDUC ’20), to discuss her book in ASL for Pitt Magazine. He is a Pitt alumnus and professor of sign language education at Gallaudet University, a renowned educational institution for the deaf and hard of hearing.

Booth also performed a reading from the prologue of “The Invention of Miracles,” which is accompanied here by an ASL interpretation provided by Felicia Williams, also of Gallaudet University.

“When hearing people insist on deaf people using English, even if their preferred language is ASL, we are essentially saying: My comfort is more important than your inclusion,” says Booth. “We might even be saying: My power to control my words is more important than your power to control yours. I find it’s important to challenge a power dynamic that prioritizes the comfort and control of hearing people, including my own.”

Q&A with Katie Booth: Deaf Culture and Alexander Graham Bell

Read a transcript of the interview here.

Listen and Watch: Excerpt from “The Invention of Miracles”

In the next two videos, Katie Booth reads an excerpt from her book and, separately, interpreter Felicia Williams translates the excerpt into American Sign Language. Read a transcript of the excerpt here.

This story is part of Pitt Magazine’s special Summer ’21 digital issue.