My father’s beatings were like lightning strikes. Powerful, fast, and unpredictable. He held his anger so tightly that, when it finally overtook him, the force was bone-shaking. He punched me like I was a grown-ass man. He went blind with rage and just punched with all the strength of a steelworker. It never took more than one to lay me on my back, windless. Then he would dare me to get up. I never did.

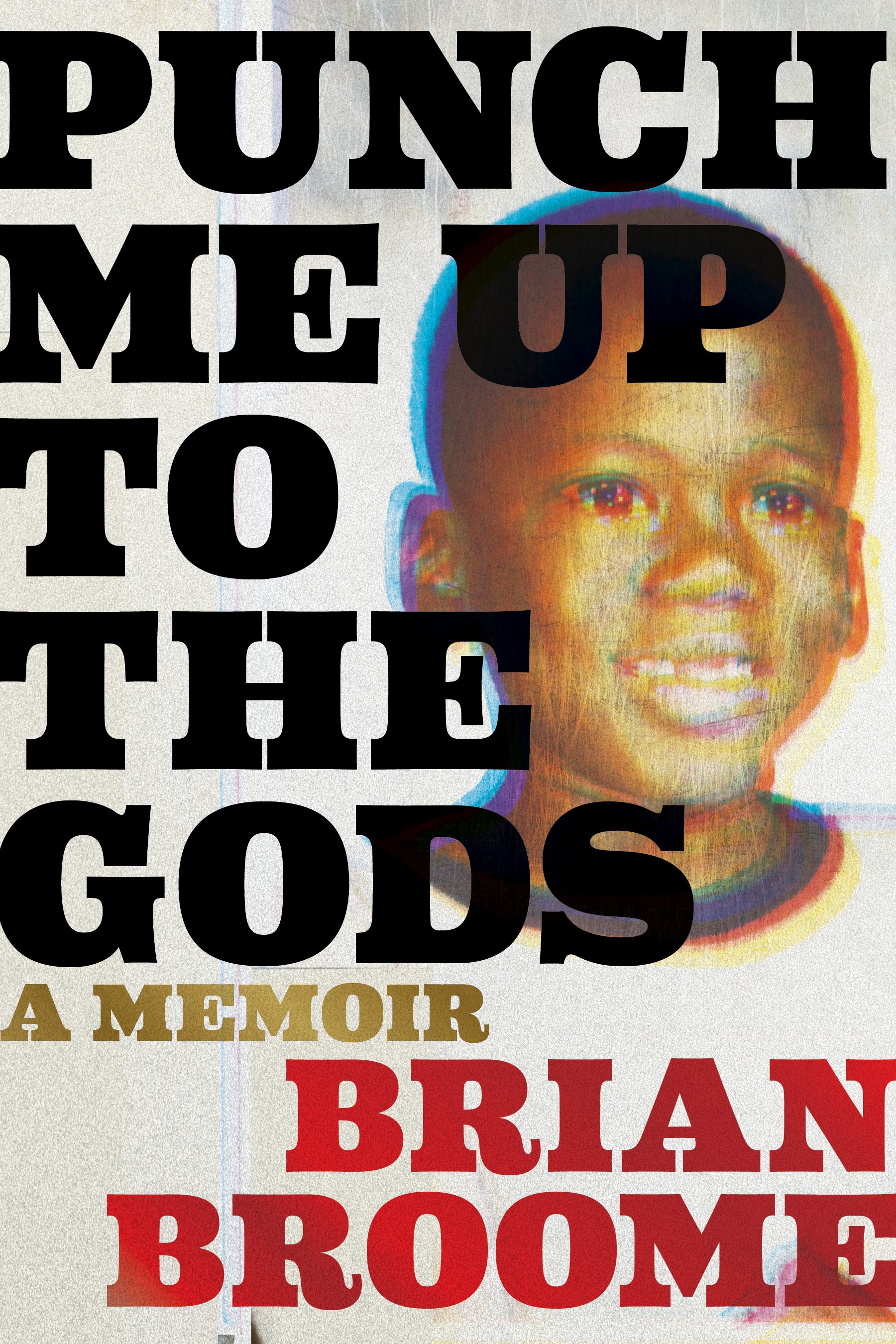

— Excerpt from “Punch Me Up to the Gods,” by Brian Broome

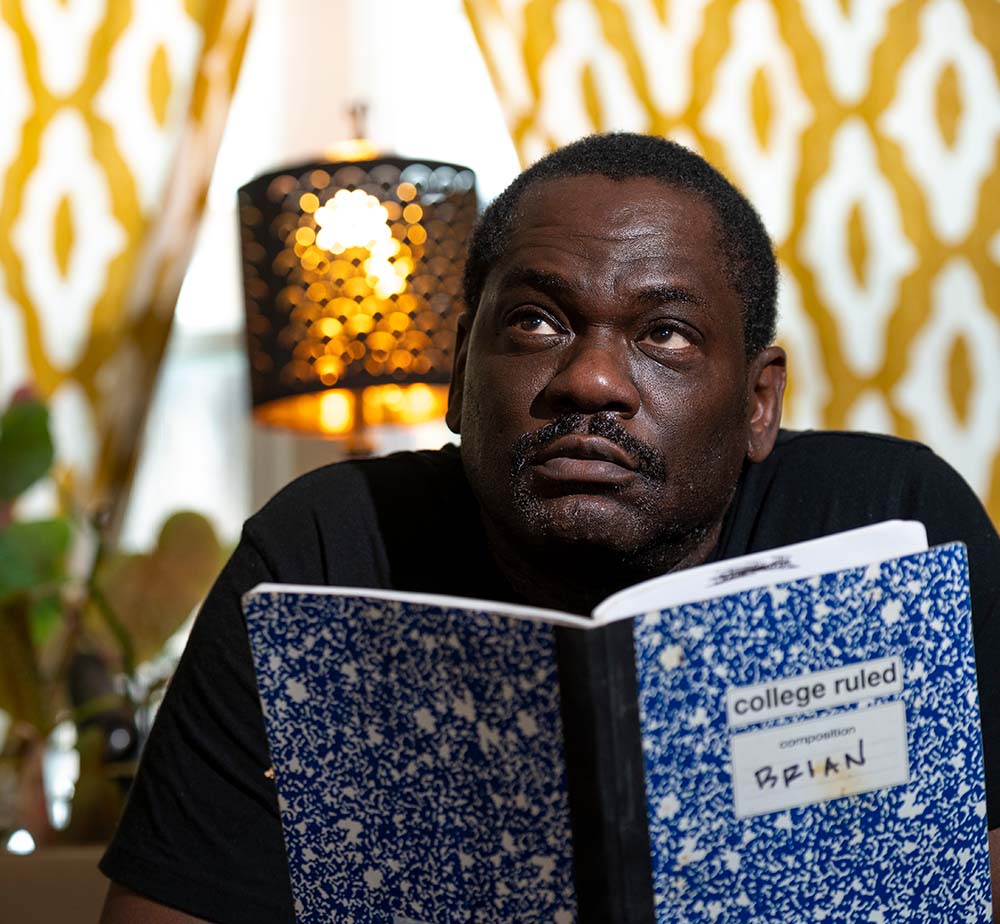

Oh, how the boy loves writing. He writes on the weekends. He writes after school. He writes in the middle of the night, careful not to wake his older brother who also sleeps in the family’s living room. If it’s a nice day, when other kids run around at a nearby field, the 10-year-old sits in the backyard under the shade of the trees — writing, writing, writing.

He writes about his life, chronicling summer days with his best friend. He scribbles down his secrets, such as the teachers he loves and those he can’t stand. The pages are testing grounds for new words he’s plucked from the encyclopedia.

Musing after musing goes into Brian Broome’s pink diary, which has a flower blossoming in one corner and a matching pen. His biggest secret, however, never makes it onto the page. To write it out, the young boy fears, could get him in big trouble.

The secret is that he has crushes on boys.

Growing up is already such a struggle for Broome, simply because he’s Black in a predominantly white, working-class northeastern Ohio town in the 1980s. He can’t write that he’s gay, too, even in the most guarded of places.

One day, an older cousin sees him with his diary and cruelly taunts him. Writing, Broome’s cousin insinuates, is not a manly thing, especially in a pink diary. In Warren, Ohio, Black young men should be rough housing, playing sports, and chasing after the girls from the nearby housing projects.

Ashamed, Broome ditches the pink diary and starts scrawling his thoughts in dull-colored spiral notebooks. But he still gets harsh scoldings from his family. He shouldn’t be writing. It isn’t masculine. It’s a waste of time. When he’s a grownup, writing won’t provide an opportunity to pay the bills. He’ll need to do something bankable, they tell him, like joining the military.

Wanting to get his life on track, Broome does what everyone tells him to do: He stops writing. It’s a loss that cascades into other losses. Slowly, everything that brings him joy — turning cartwheels, cheerleading, jumping rope — just stops. Almost every flake of his confidence, of who he is, melts away, too.

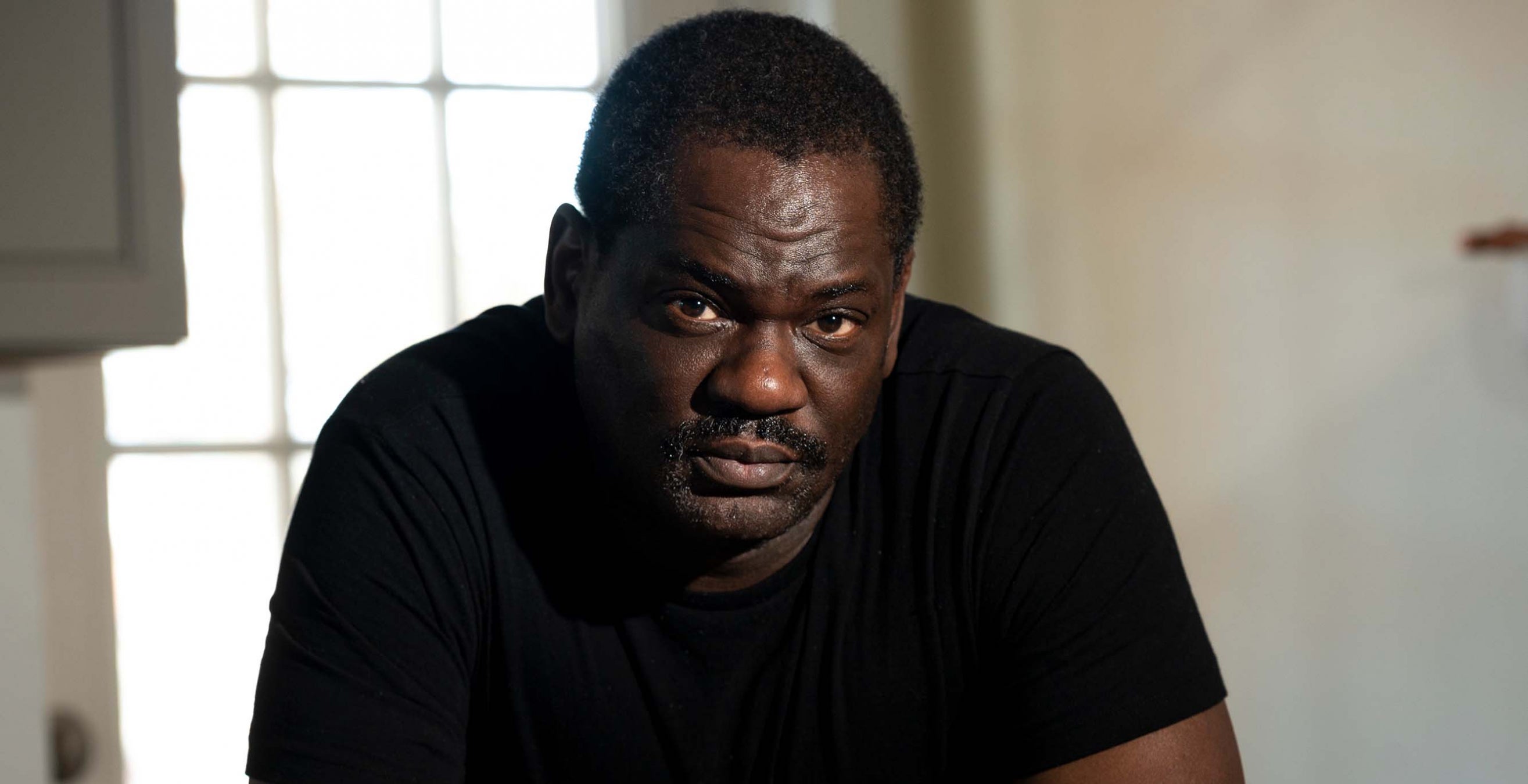

Three decades later, Broome has found his way back to writing — with a bang. His memoir, “Punch Me Up to the Gods,” (Mariner Books) was released in 2021 to critical and reader acclaim.

Three decades later, Broome has found his way back to writing — with a bang. His memoir, “Punch Me Up to the Gods,” (Mariner Books) was released in 2021 to critical and reader acclaim.

Praise for the memoir, which was written, in part, while he earned a Master of Fine Arts degree in nonfiction writing at Pitt, has been momentous. It earned Broome the prestigious Kirkus Prize for Nonfiction, which comes with a prize of $50,000. The editors of The New York Times Book Review named it one of the “100 Notable Books of 2021.” Shortly after the book’s debut, it was named “An Amazon Best Book of May 2021.”

But getting here — as his memoir recounts in raw detail — required a slog through self-loathing, addiction and anguish.

Broome couldn’t stop being gay. He couldn’t stop being Black. And so he couldn’t stop feeling like a misfit. Nowhere was safe. To try to belong at school, he “performed” for white classmates, dancing on cue for their applause. But if he broke his family’s curfew at the Red Caboose dancehall, none of the cheering white students dared to give him a ride home.

And the Black kids shunned him because he was queer. Everywhere he turned, he was hit by a wall of hypermasculinity. Broome was told he could only be a man if he was strong, dominant and heterosexual. He was none of those. He was awkward, he wanted to study ballet, he played with dolls, and he found great pleasure in words.

His father, an increasingly despondent laid-off steelworker, didn’t know what to do with him. He scolded Broome for “acting like a girl” or sometimes violently shook him, thinking an “ass-whuppin’” might fix him.

In one angry rebuke, from which Broome drew the title of his memoir, his father told him that he needed to be “punched back up to the gods,” as though, the writer now muses, Heaven’s angels would send him back as he was expected to be: more masculine; less himself.

His parents eventually divorced but even with his dad out of his life, Broome continued to endure relentless judgments in school and throughout the community.

“I slowly learned to absolutely despise myself,” he remembers. “I hated everything about me. I wished myself dead.”

Knowing that he needed to escape, he worked to get good grades in high school so he could go to college. With help from a loan his mother took out, he cobbled together enough funding to enroll in the University of Akron. But even there, he says, it was more of the same.

In the fall 1988, after about four weeks at Akron, he fled in the middle of the night, running from his shame and four baseball-jock roommates who had discovered a flier in his room advertising the university’s gay and lesbian task force. They made it extremely clear, Broome recalls, that a gay roommate wasn’t welcome in their off-campus apartment.

Back in Warren, depression descended. He knew he couldn’t stay there. Not yet 20 years old, he decided to head to Pittsburgh, about 90 miles away. He’d been there once — to march at Three Rivers Stadium with his high school band — and he thought it might be diverse enough to make a Black gay man feel at home.

As his mother drove him across the Fort Pitt Bridge, he says he was filled with hope and optimism at the prospect of finding love and friendships. But self-loathing got in the way.

Even though he found a more open, welcoming community, he turned to alcohol and drugs. Spiraling downward, he never considered returning to writing. Instead, he focused on the nightlife, at one time earning money dancing at clubs. He didn’t find love, either — mostly just intimacy with strangers.

Nothing much changed for more than two decades, aside from menial jobs. Then, one winter morning after an evening of partying, he came to inside a stranger’s doghouse, its rightful occupant chomping on his ear.

At that moment, he says, he realized he had hit rock bottom.

A few weeks before Christmas 2014, he checked himself into a drug rehab center on the outskirts of the city. The first night, he thought of just walking away. But the no-nonsense nurse at the front desk talked him into staying.

A few weeks before Christmas 2014, he checked himself into a drug rehab center on the outskirts of the city. The first night, he thought of just walking away. But the no-nonsense nurse at the front desk talked him into staying.

In rehab, as his roommate snored, Broome reunited with his first love.

“I just started writing,” he says. “It was, like, automatic, because I had kind of lost everything. There was no friend to call. There was no noise. There was no TV. There was no distraction. It just felt natural to pick up a pen and paper and start writing my story.”

The words flowed out of him as he reflected on reaching this low point, on his never-ending feelings of being rejected, and on what he needed to heal.

After about a month, Broome was released from rehab, and he went home. Alone. He hid there at first, because he was afraid of relapsing. He went out only to work his long-time job dispatching emergency roadside assistance from within the three dreary walls of a cubicle.

But he kept writing. On Facebook, he drafted heart-warming, provocative short stories and whip smart essays commenting on social justice news, sharing sweet moments with the sex worker friend he chatted with at the bus stop, or gossiping about his neighbors’ colorful antics. A few people began commenting on his writings, then a few more. Before long, Broome had nearly 7,000 social media followers of his literary talent.

He returned to longhand writing, too, scribbling in notebooks while riding the bus around Pittsburgh. In one instance, he witnessed a Black father telling his young son, who had just fallen, to “shake it off,” to stop crying, and to “be a man.” The scene jolted Broome’s memory about his interactions with his own dad.

The more he wrote, the less he could bear his day job. When he was fired after an argument with a supervisor, he felt relief.

Broome, at age 42, finally felt free to build a writing career. He enrolled in literature and journalism classes at the Community College of Allegheny County in 2015, eventually transferring to the newly co-ed Pittsburgh liberal arts college, Chatham University. Before graduating in 2017, he won a creative nonfiction contest with a story about his bus rides.

He used that same piece as a writing sample when applying to Pitt’s graduate writing program. His application, his talent and his story stood out, says English Professor Michael Meyer, who then served on the masters of fine arts (MFA) admission committee. Broome was one of three nonfiction writers chosen for the program that year. Earning the spot meant he would have three funded years to dedicate to intensive creative writing study and teaching, culminating in his own book-length manuscript, or thesis.

At first, Broome felt out of place beginning graduate school in his late forties. He worried that he looked like the oldest student on campus as he rushed through the Cathedral of Learning on his way to class. Nevertheless, he plodded on, befriending a circle of instructors and other writing students — themselves from varied walks of life — who nurtured him along.

At first, Broome felt out of place beginning graduate school in his late forties. He worried that he looked like the oldest student on campus as he rushed through the Cathedral of Learning on his way to class. Nevertheless, he plodded on, befriending a circle of instructors and other writing students — themselves from varied walks of life — who nurtured him along.

He took a contemporary nonfiction readings course with Meyer, who recalls that Broome’s classmates were genuinely interested in Broome’s reactions to the stories and ideas they explored. Over time, says Meyer, “I think Brian felt more comfortable believing that, ‘I do belong here, on this island of misfit toys.’”

At Pitt, reminisces Broome, he rediscovered the joy of writing but also gained knowledge in the artistry and business of the craft, exploring authors’ writing techniques, such as story development, sentence structure and sense of empathy. He learned that once there’s a revision, there’s another, then another.

Shoulder to shoulder with peers in the MFA program’s writing workshops, Broome saw his memoir — which was then his graduate thesis — come into focus. He began to pull drafts from his rehab writing, determining that the core of his story was “how I was raised to be masculine and raised to be a man.”

Ultimately, this work would become “Punch Me Up to the Gods.”

For many graduates of Pitt’s MFA program, Meyer notes, it takes about seven years from thesis manuscript completion to earning a book deal. Not so for Broome. As his graduation neared, Meyer laughs that Broome’s thesis committee was practically putting notes not on a manuscript but on final-page proofs that were coming from the writer’s publisher.

His words, once stifled, were now in full flow — and the world wanted to read them.

While his memoir went to press, he kept writing, publishing locally and nationally, using his lyrical voice and keen observations to explore issues of race, sexuality, gender and class privilege. On and off social media, he developed a loyal following. It was the antithesis of those boyhood days in Ohio.

His triumphs culminated with the release of his memoir to rave reviews. Among others, Augusten Burroughs, the New York Times best-selling author of “Running with Scissors,” called Broome’s memoir “some of the finest writing I have ever encountered and one of the most electrifying, powerful, simply spectacular memoirs I — or you — have ever read.”

In October 2021, Broome was home alone for the live-streamed Kirkus Prize ceremony. When it was announced that he had won, he was caught off guard.

“I do not know what to say,” he said, tearing up, to the digital crowd. “I’m sitting here by myself because I thought there’s no way that this would be happening to me.”

Broome couldn’t stop being gay. He couldn’t stop being Black. But he could stop hiding from himself.

In a way, life did punch Broome back up to the gods — but not to be remade in anyone’s narrow vision. Instead, he returned restored, a survivor, a stronger version of who he was meant to be. And the parts of himself he once found so shameful that he couldn’t admit to them in even the most secret of places, have helped him build a life that brings him pride.

Recently, Broome took a position as a distinguished visiting writer in at Saint Mary’s College in Moraga, California, where he’ll teach, as well as create. Working with up-and-coming writers — just like sharing his book with readers — makes him feel as though he is connecting to something greater than himself.

It reminds him of that night in rehab when he first sat down to write again. He felt like he was the loneliest person in the world — the only person with the kinds of problems he faced.

“And then,” he says he discovered, “you read books, and you’re not alone at all.”

This story was posted on March 1, 2022. It will appear in the Spring 2022 issue of Pitt Magazine.