Mijung Park, a professor and nurse, lives in downtown Pittsburgh near the city’s Hill District. She often drives through that neighborhood, usually on her way to work. During the short trip, she notices broken windows, graffiti, abandoned homes, and shuttered businesses along some Hill District streets, in an area that is struggling to recover from urban distress. Fewer than two miles ahead, she enters an affluent neighborhood in a historic district situated just above the University of Pittsburgh’s bustling Oakland campus. There, she drives past well-preserved homes and manicured lawns. The difference in physical environments, she says, is apparent.

As a Pitt researcher interested in population health, Park wonders whether the stark socioeconomic differences in the two neighborhoods might have other striking consequences as well. What she later discovers when pursuing that question surprises her—and makes international news.

This wouldn’t be the first time Park’s instincts created an unexpected outcome. As a young woman enrolled in Ewha Womans University in her hometown of Seoul, South Korea, she hopped on a crowded subway to drop off paperwork declaring her intention to major in theoretical astrophysics. “Like Einstein,” she clarifies.

Entering the subway car, she encountered a man with a disability. “The entire row was empty, because nobody wanted to sit next to him,” Park recalls. “So I sat right next to him, and we talked for some time.” On the spot, she realized she wanted to find a way to help those who are marginalized by mainstream society. She changed her major from physics to nursing before the ride was over.

Since then, Park has devoted herself to improving the health of others, especially those who are “the most vulnerable people.” After completing her bachelor’s degree in nursing science in 1994, she worked as a psychiatric nurse at the Samsung Medical Center in Seoul. She frequently interacted with family caregivers and saw the impact of illness not only on the patient but also their loved ones.

The experience shaped the content of her master’s thesis in nursing, also completed at Ewha Womans University, where she studied how patients and their family caregivers together cope with severe mental illness. Then, she had the opportunity to participate in the Family Nurse Practitioner program at the University of California, San Francisco, where she earned a PhD in 2007. It was there she first encountered health disparities in the U.S., which would become the cornerstone of her research.

The experience shaped the content of her master’s thesis in nursing, also completed at Ewha Womans University, where she studied how patients and their family caregivers together cope with severe mental illness. Then, she had the opportunity to participate in the Family Nurse Practitioner program at the University of California, San Francisco, where she earned a PhD in 2007. It was there she first encountered health disparities in the U.S., which would become the cornerstone of her research.

While earning her degree, she worked as a psychiatric nurse at San Francisco General Hospital, where she often served the poor and uninsured, including the homeless and immigrants. Among her duties, she evaluated patients to see whether the hospital could admit them for immediate psychiatric treatment.

“That’s when I first learned about insurance issues,” Park says. Insurance coverage was something she had never considered in South Korea, where universal healthcare was in place. “Essentially, I witnessed the detrimental impact of not having insurance on people's ability to manage their health. Until then, I never thought that one factor could make or break a person’s health or quality of life.”

Seeing the hardships individuals faced fueled Park’s interest in how social structure and policy issues—like access, cost, and quality of care—impact health. During postdoctoral training at the University of Washington, she conducted research to explore whether contextual factors influence an individual’s health. In the health disciplines, she says, “contextual factors” refers to any external circumstance that might affect care—socioeconomics, cultural background, the organization of health care systems, the quality of support networks, and so on.

“It has a trickle-down impact,” says Park about what she discovered. Contextual factors affect mental health, which, in turn, affects physical health. For Park, who was thinking at the community systems level, it was an important realization: Don’t discount how the complexity of individuals’ lives can influence their health.

That lesson may be what prompted Park’s research curiosity on her regular drives through Pittsburgh’s Hill District. She joined Pitt’s faculty in 2013 as an assistant professor of health and community systems in the School of Nursing, which is ranked 5th in the nation for the quality of its graduate programs. She was drawn here, she says, because of the University's robust research on older adults and their caregivers, along with a vigorous health care services network.

The stark socioeconomic contrasts she observed as she drove between two neighborhoods on the way to her campus office made her wonder—could “contextual factors” in a neighborhood affect an individual’s health? She decided to approach that question in a truly new way.

Park was aware that prior research by others had established that people who experience disenfranchisement—the lack of political power to determine one's own life and destiny—have higher levels of stress hormones. And, the heavy toll that crime and poverty take on health is well documented in medical literature. But Park chose an even bigger research challenge—what effect might these circumstances have on a biological marker: DNA.

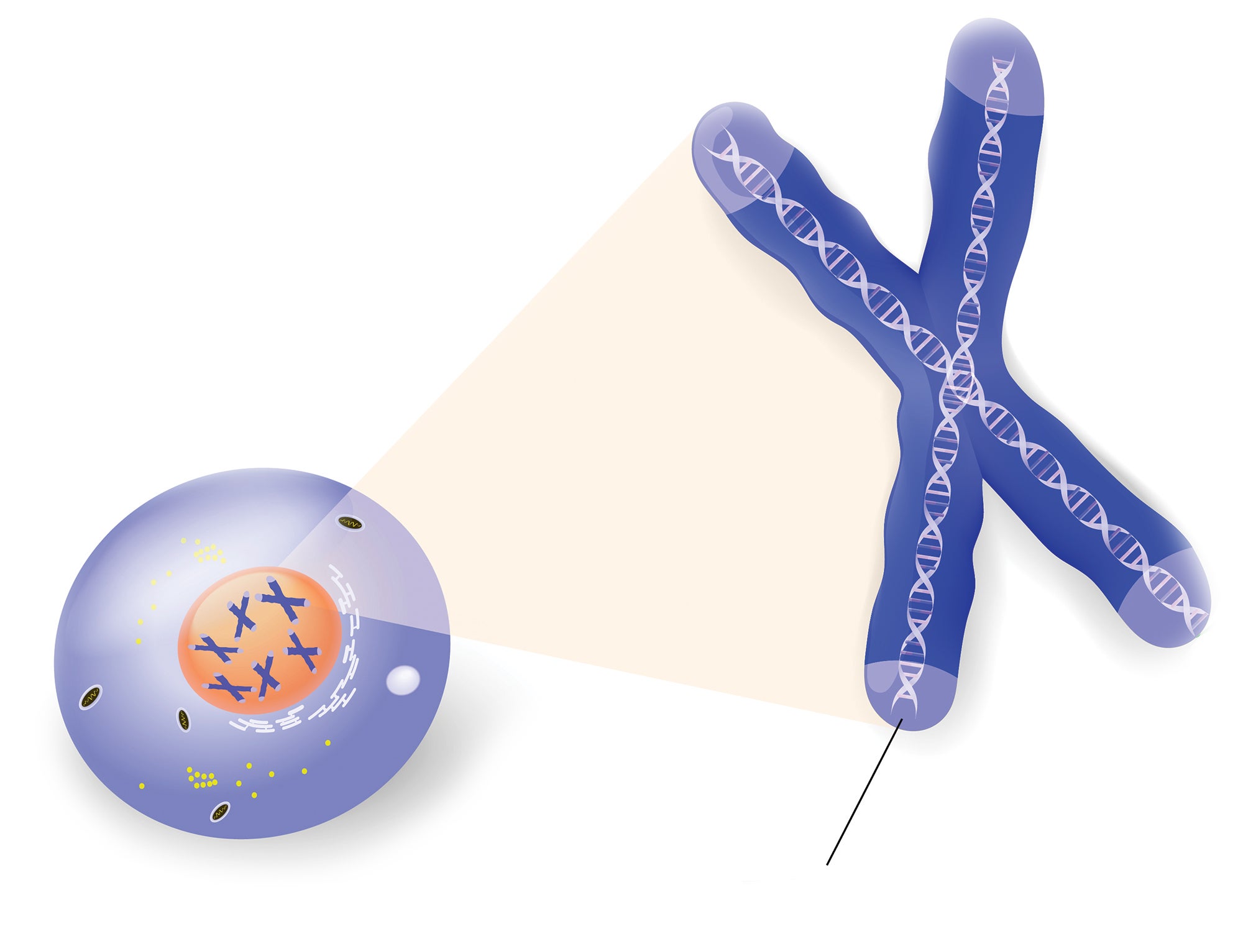

She focused her study on telomeres, stretches of DNA that are often compared to the plastic or metal tips at the ends of shoelaces. Telomeres serve as the “caps” at the end of chromosomes, protecting them from damage during replication. Each time cells divide, telomeres shorten, as they are not copied fully by enzymes. The process is associated with aging, illness, and death, a discovery that was awarded the 2009 Nobel Prize in Medicine. Stress—including physical and mental illness and lifestyle factors—is known to accelerate telomere shortening. Park hypothesized that living in a disadvantaged neighborhood could, too.

Though Park suspected a correlation, just how significant it turned out to be surprised her. Collaborating with Dutch investigators of the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA), Park and colleagues at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Aging Institute analyzed the data from 2,981 Dutch individuals aged 18 to 65. The research team controlled for individual characteristics, including age, gender, income, and educational attainment, allowing the researchers to focus on the link between the participants’ perceptions of their neighborhoods’ quality and the length of telomeres. Participants answered questions about their fear of crime, noise, and vandalism in their neighborhoods and gave blood samples so their telomere lengths could be measured.

Though Park suspected a correlation, just how significant it turned out to be surprised her. Collaborating with Dutch investigators of the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA), Park and colleagues at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Aging Institute analyzed the data from 2,981 Dutch individuals aged 18 to 65. The research team controlled for individual characteristics, including age, gender, income, and educational attainment, allowing the researchers to focus on the link between the participants’ perceptions of their neighborhoods’ quality and the length of telomeres. Participants answered questions about their fear of crime, noise, and vandalism in their neighborhoods and gave blood samples so their telomere lengths could be measured.

The team found that, compared with those who reported living in high-quality neighborhoods, those who perceived themselves as living in low-quality neighborhoods had shortened telomere lengths equivalent to 12 years of biological age. In other words, residents of disadvantaged neighborhoods were 12 years older at the cellular level than their more advantaged counterparts, despite their actual ages being the same. The study, “Where You Live May Make You Old,” was published in the journal PLOS ONE in 2015.

Park is careful to emphasize that the link between a neighborhood and telomere length found in the study is correlative, not predictive. Researchers cannot deduce, for example, that moving from an affluent neighborhood to a disadvantaged one would produce accelerated cellular aging (shortened telomere length). Also, an individual’s cells being 12 years older does not necessarily mean that the person will die 12 years sooner.

However, science’s understanding about telomeres is rapidly evolving. Numerous studies have found that accelerated telomere shortening is associated with a higher risk of cancer, heart disease, and other medical conditions.

“All those outside factors that make us unhappy can actually have a cellular impact,” Park says about the study’s conclusions. “Those are interesting findings.”

Park’s work received international attention, covered by media outlets including the New York Times, CBS News, and the UK’s Telegraph. Ultimately, she attributes the study’s success to the public’s “growing awareness” of wealth gaps, which are increasingly visible at the neighborhood level. A recent Century Foundation study found that, in the United States, the number of people living in concentrated poverty doubled in the last 13 years, increasing from 7.2 million to 13.8 million—the highest number ever recorded.

At a time when inequality looms large in the national conversation, having scientific evidence of its impact on health resonates. Park believes it’s easy for people to see the study’s relevance in their own lives. “Feeling safe and being able to walk around safely in your own neighborhood are fundamental rights of all residents," says Park.

Beyond her contribution to telomere science, Park—who also holds a Master’s in Public Health from the University of Washington—hopes her research can be used to shape public policy including, perhaps, urban housing and planning.

For Park, progress requires getting past traditional constraints in the health sciences to create a more dynamic picture of health that accepts the reality of multiple influences far beyond the physical.

“In medicine and health research, we tend to focus on the relationship between one cause and one health outcome. It’s actually considered good science: if your formula is simpler, that’s better,” Park says. “But human life is not that simple.”

There are multiple layers of factors that affect health, including politics and policies, notes Park. If a neighborhood feels unsafe, she explains, then those residents may avoid walking for exercise, which is an easy, cost-free way to improve health.

There are multiple layers of factors that affect health, including politics and policies, notes Park. If a neighborhood feels unsafe, she explains, then those residents may avoid walking for exercise, which is an easy, cost-free way to improve health.

“Creating healthy neighborhoods needs political will to allocate resources,” says Park. “Researchers should pay close attention to such factors.”

And that’s why she’s drawn to work that has the potential to shape health policy, affecting large populations of people. Park’s current research project is exploring ways to help family members care for older adults who have depression combined with multiple other medical conditions. Such coexisting health issues in the elderly amount to a serious public health problem, says Park.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report that depression risk increases for those suffering from an illness; about 80 percent of older adults in the United States have at least one chronic health condition, and 50 percent have two or more. Because they often have multiple doctors, coordinating health care gets more complicated.

“But this population is very exciting,” Park says, “because I can help them.”

Her new research is also looking for ways to better integrate the caregiving provided by family members with the larger medical system. Her current study—focusing on family-centered care of older adults with multiple chronic conditions—recently received a prestigious grant from the National Institute of Nursing Research.

Park believes science should embrace a more holistic view to achieve a broader social impact. Contact with policymakers and community members—stakeholders at all levels—will become increasingly essential, she says, if research is to improve health and quality of life. It’s complex, but it’s possible; and Mijung Park is driving forward.

Cover image: Mijung Park

This story appears in the Summer 2016 issue of Pitt Magazine.