The plane that carried Charles Lindbergh on the first trans-Atlantic flight is suspended high above a gallery in Washington, D.C.’s Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. Its long, silver body appears frozen in flight. A nearby display on the aircraft, named the Spirit of St. Louis, is full of information. But when Margaret A. Weitekamp (A&S ’93) introduces the plane to visitors, she tries to get beyond simple recitation of facts. She asks a surprisingly tricky question: “Where’s the windshield?”

Is there no windshield? Suddenly, visitors look all around. How did Lindbergh see? An object that once seemed static is now a puzzle to be investigated, a site of discovery.

“The best objects tell multiple stories,” Weitekamp says. “They allow us to connect to the person who designed and built and tested the thing or to a story of a larger national effort.”

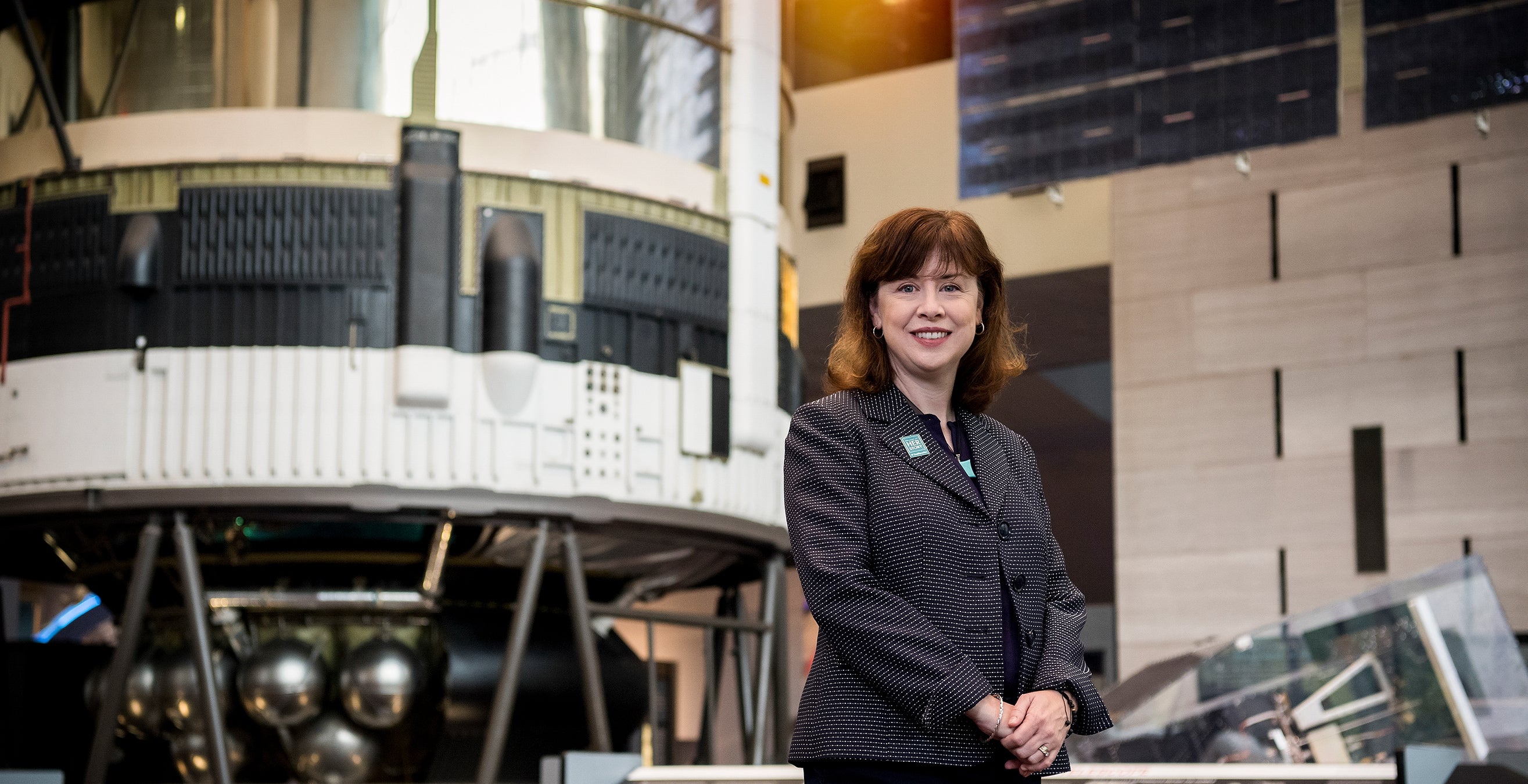

As the curator and recently appointed department chair of the museum’s Space History Department, Weitekamp uses a passion for inquiry and storytelling to bring to life the more than 5,000 artifacts under her purview. The work involves planning exhibitions and researching a wide variety of air- and space-related subjects, from some of the world’s earliest aircrafts to the studio model of the starship Enterprise from the original Star Trek television show.

Her goal is to inspire people to ask questions about the past, which, in turn, can ignite a re-examination of the present. It’s the same kind of exploration that first connected her to history. As a first-year student at Pitt, she enrolled in Maurine Greenwald’s U.S. Women’s History survey, which taught her not to trust inherited knowledge, but to turn to primary sources and use them to probe further.

It’s not just turning back to these sources that makes history more interesting; doing so also resists the prejudices of the present. The story of flight “is an international story, and is a story of men and women,” explains Weitekamp, who authored Right Stuff, Wrong Sex, a book about America’s first Woman in Space Program. The details of Weitekamp’s work reveal history as it is: interconnected, complicated, full of astonishing feats. And a missing windshield.

Once people realize that the Spirit of St. Louis doesn’t have a windshield, they begin to explore. They find a periscope sticking out the port side of the plane, and the curator explains that Lindbergh used that and looked out of the side window as he navigated for 33 hours in what was, in Weitekamp’s words, a flying gas can.

“I think it makes the physical feat of that trans-Atlantic crossing even more remarkable,” she says. “It gives you a new appreciation for the determination of a pilot who could fly that route in those conditions.”

No matter the artifact she’s sharing, making room for new appreciations—while shaking the dust off of history—is Weitekamp’s specialty.

Cover image: Margaret Weitekamp

This article appeared in the Winter 2020 edition of Pitt Magazine.