It’s a new day. The diligent young man rises early, a habit built from a childhood spent attending Baptist Sunday school. He says his morning devotions, slips on his shirt and tie — presenting an image of dignity is important to him — and jumps into his gently used Chevy.

He drives the short distance from his home in the city’s Garfield neighborhood to the University of Pittsburgh, where he’s a busy and popular student. Much of his day is spent studying and taking classes in the Cathedral of Learning. Afterward, he heads downtown to Liggett’s Drug Store, where he works as a dishwasher at the soda fountain. He earns 28 cents an hour.

It's the spring of 1948 and a sense of optimism seems to hover over William Aldophus Granberry Fisher. A bookish, motivated student, this is his second stint at Pitt. He first enrolled in 1942 but was soon conscripted to serve in World War II. When he came back to campus in 1946 — this time with help from the GI Bill — he returned to a changing social landscape. The post-war era saw a push for civil rights and new avenues of equality in society and on campus. Fisher embraces it all.

He bounds through Pitt courses in history, English and psychology. He’s practically in school year-round, taking classes in the fall, spring and summer semesters. He’s excited to expand his knowledge and readiness to be an educator, forging a career of distinction and social mobility.

Shepherding this aspiration is the community he finds in Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Incorporated, the first Black male fraternity on Pitt’s campus. The brotherhood provides Fisher a deeper belonging and reinforces a personal belief in “being the master of your fate.”

For Fisher — and for hundreds of others — the combination of a college education and the historically Black Greek-letter fraternity/sorority system created an incubator of Black talent. For more than a century, empowered by Pitt degrees and charged with values of justice and service to others, the men and women of Black Greek-letter organizations entered society as pioneers in medicine, education, business and law.

In 2021, a special monument — the National Pan-Hellenic Council plot — was established on the University’s Pittsburgh campus to celebrate the unique legacy and cooperation of nine of the Black fraternities and sororities. It sits between the William Pitt Union and the Litchfield Towers. Pitt is among just a handful of predominately white campuses that recognize the contributions of these organizations.

Vice Provost for Student Affairs Kenyon Bonner attended the monument’s unveiling during Homecoming that year.

Vice Provost for Student Affairs Kenyon Bonner attended the monument’s unveiling during Homecoming that year.

“In my 17 years at Pitt, it’s one of my favorite memories,” he says. “Seeing that many Black alumni come back to campus to celebrate something that was designed for the Black community and the Black student experience.” Many of the alumni who attended the unveiling, Bonner notes, are members of the Greek-letter organizations and “really see the connection that Pitt values its Black Greek-letter fraternities and sororities.”

Standing amid the crowd of more than 400 was Fisher, one of the oldest living members of a Pitt fraternity.

Fisher, the son of a garbage hauler, did not have a sure pathway to success. But Pitt and the Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity gave him confidence that he could become something more. Back in 1948, he sees nothing but hope before him. Why shouldn’t he?

Fisher, the son of a garbage hauler, did not have a sure pathway to success. But Pitt and the Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity gave him confidence that he could become something more. Back in 1948, he sees nothing but hope before him. Why shouldn’t he?

His past is evidence of his resilience and determination. Fisher grew up in the city’s East End. Fisher’s grandmother, Nora Durham, raised him and his little brother after their mother died at 24 from tuberculosis. His father wasn’t around much, and his grandfather didn’t make anything easier. Sometimes, he forced the brothers out of the house and made them sleep in a nearby garage.

Through it all, his grandmother stoked a noble calling for her grandson. She called him her “Little Black Prince,” a nickname that instilled in him a sense of pride and the aspiration that he could overcome racial oppression.

When Fisher grew up, segregation — in housing, in the military, in public accommodations — was the law. Black people couldn’t sit in certain restaurants, enter certain hotels or work certain jobs.

Despite it all, the Little Black Prince rose to every occasion. At Pittsburgh’s Peabody High, a school full of the children of ethnic immigrants and African Americans, he was editor of the yearbook, president of the Latin Club and valedictorian of his class.

He came to Pitt with help from the competitive Barr-Brown Scholarship. Joseph M. Barr was an influential politician who eventually served as Pittsburgh’s mayor. Homer Brown was a Pitt law school alumnus and a pioneering attorney who became the first Black judge in Allegheny County.

“I was thrilled to be at Pitt,” recalls Fisher. “Getting accepted meant I could live up to the expectations that my grandmother had for me to succeed.”

The scholarship, and resulting connection to Brown, introduced Fisher to all he could become — distinguished, respected, accomplished and a gentleman of Alpha Phi Alpha, the nation’s first Greek-letter fraternity for Black men, founded in 1906 at Cornell University. Omicron, the fraternity’s 14th chapter, was established on Pitt’s campus in 1913.

I admired all of them. They were fiery and fought for racial equality. I saw a fortitude in that. I wanted to join the Alphas.

William Fisher

Members of the Alphas included Paul Simmons, then a recent Pitt graduate who had headed to Harvard University and would become one of the nation’s first Black federal judges. Another member was Frank Bolden, a journalist and pioneering WWII correspondent. There was Robert L. Vann, too, the editor of the internationally heralded and politically influential Pittsburgh Courier newspaper. Those three were just a few of the Alphas Fisher says he looked up to:

“I admired all of them,” he says of the Alpha brothers. “They were fiery and fought for racial equality. I saw a fortitude in that. I wanted to join the Alphas. They represented what I wanted to become. I also wanted a place where I felt I belonged and was welcomed.”

The Alphas would be key in helping Fisher find a meaningful path in life.

He was initiated into the fraternity in 1948 and soon became its president. Fisher juggled his Alpha responsibilities with being in the University’s Interfraternity Council, the Men’s Council, the Debate Club, and serving as a Pitt Player, where he was the only Black man in the ensemble. In 1948, he also became the first Black male student at Pitt to be recognized for exemplary leadership by being elected by his peers to an honorary group then called the Pitt Hall of Fame. His name is inscribed in stone along the walk of achievement from Heinz Chapel to the Cathedral of Learning.

On campus, the Alphas pushed to have the first traffic light installed on Fifth Avenue in front of the Cathedral to help with student safety. Off campus, they gathered in a fraternity home in the city’s Hill District, where they studied, organized voting campaigns, and hosted cultural events, such as sponsoring a performance by Marian Anderson, the acclaimed Black concert vocalist.

When Black Greek-letter organizations developed on predominately white campuses, they created an extracurricular gathering space where African Americans were no longer in the minority. They made a place where their culture was celebrated, and where Black students were girded against historically racist structures that could complicate their academic journeys.

In a sense, says Clyde Wilson Pickett, Pitt’s chief diversity officer and vice chancellor for Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion, the organizations were the precursors of the work that his office does today. They were a diverse, organized body on campus pushing for change and greater access.

“That’s the history of why these organizations were created,” Pickett says, “to provide that structure of support, to bring folks together, to push toward success, and ultimately progress and change. They are a lasting legacy of what it means to be a part of the community, to work toward a common goal of completing your education, achieving, and making change. So, in many ways, they are connected to the legacy of pursuing equity, inclusion and belonging.”

Pickett was an undergraduate student at the University of Kentucky when he was initiated into the Kappa Tau chapter of Kappa Alpha Psi Fraternity, Incorporated, one of the nine Black Greek-letter fraternities in the United States known as the Divine Nine. He called the experience “transformational” in how it prepared him for leadership, student activism and for speaking up for himself and others.

The Divine Nine are evidence, says Pickett, of what happens when universities contribute to cultivating all minds. “It really shows that when you invest in the whole community, it benefits the whole society.”

Promoting belonging, civility, respect, dignity, and inclusion is much of the work around creating equity, says Pickett, and it’s much of what comes with working directly with Black alumni, particularly the African American Alumni Council, where many members are part of historically Black Greek-letter organizations at Pitt.

“When we work with Black Greek-letter organizations," Pickett says, "we cultivate the minds that go on to influence and guide communities all around the world. So, when we do that, we're preparing those who will change the world.”

About seven years ago, more widely sharing the story of Black Greek-letter groups on Pitt’s campus became an informal mission of change for Kenyon Bonner. That’s when he had a conversation with an African American teenager who told him that, while visiting Pitt, he had no clue that Black Greek life was a part of the campus.

Later, another incoming student confessed he didn’t even know Black Greek-letter organizations existed.

Bonner wanted to change that. He’s a member of the Divine Nine. He joined Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Incorporated, as a graduate chapter initiate and recalls the “leadership and professional brotherhood” the experience provided him. He thought that Pitt could do a better job highlighting Black Greek-letter life on campus, something that has been a part of the University for 110 years — more than 10 years before the first brick was laid in the Cathedral of Learning.

Bonner wanted to change that. He’s a member of the Divine Nine. He joined Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Incorporated, as a graduate chapter initiate and recalls the “leadership and professional brotherhood” the experience provided him. He thought that Pitt could do a better job highlighting Black Greek-letter life on campus, something that has been a part of the University for 110 years — more than 10 years before the first brick was laid in the Cathedral of Learning.

Bonner believed that the Divine Nine monument — which was erected thanks to the advocacy and donations of many students, alumni and others — wouldn’t only honor that legacy but also encourage new students to get involved.

Today, seven of the Divine Nine fraternities and sororities have active student chapters at Pitt. Membership has declined since the days when Fisher was on campus. Yet, according to Rich Fann, associate director of the office of fraternity and sorority life at Pitt, the remaining community is “small but mighty.” They have a collective GPA of 3.4 — higher than the campus average — and log hundreds of hours in service projects on and off campus. Like the members before them, their Pitt education, paired with their Greek-letter community, ensures that they are poised to go out into the world and make a difference.

When he left Pitt in 1948, Fisher worked as a clerk and a manager for the Pennsylvania Unemployment Office in the Hill District. It wasn’t until 1955 that he took his first steps as a teacher, walking up the wide, cement stairs into Pittsburgh’s regal Fifth Avenue High School. There, he began a remarkable professional climb.

Fisher became the first to teach a class in Negro history in Pittsburgh public schools and the first to create a parent-teacher organization at a Pittsburgh public high school. Others recognized his worth early on, too. In the second year of his teaching career, he was honored as one of the 10 best teachers in Pittsburgh with the Edgar Stern Award.

It would not be long before Fisher went back to class to earn a master’s degree in education from Duquesne University. Shortly after, he soared into high-level administration, becoming a vice principal at Westinghouse High in Homewood and, eventually, returning as vice principal to Fifth Avenue High, where he stayed for 11 years.

In 1971, he again made history when he became the first African American principal of the predominately white Taylor Allderdice High School in the city’s Squirrel Hill neighborhood.

He started the job amid the tumult of desegregation. It was a tense and sometimes violent time. Fights were common and students would often leave the school to escape the aggravations, Fisher recalls. Nonetheless, he soon became a beloved and cherished principal, thanks, in part, to his warm but firm rapport with his pupils. (He earned the nickname “Hook” for his insistence that young men take off their caps indoors or else hang them up in his office.) He saw potential in each student he met and pushed them to be their best.

It was a service few would forget.

In the summer of 2022, green, black, and white balloons—the colors of Allderdice High School—were scattered around the sixth-floor ballroom in the downtown Rivers Club. The class of 1972 had gathered to celebrate its 50th reunion.

At the center of the celebration, in his suit and tie, sat a smiling Fisher. This was the first class to graduate under Fisher’s principalship and, decades later, the former students still remembered him.

At the center of the celebration, in his suit and tie, sat a smiling Fisher. This was the first class to graduate under Fisher’s principalship and, decades later, the former students still remembered him.

Two years earlier, during the height of COVID-19, a Facebook post on an Allderdice alumni page asked those who were inspired by Fisher to mail him a holiday card. He received more than 300 cards from across the nation that winter.

He told his students what his grandmother, Nora, told him: to aim for their highest place in the world. And they did. Later in life, Fisher watched as a long list of accomplished Allderdice alumni made their mark, including two Nobel Prize winners, Francis Arnold for chemistry and Joshua Angrist for economics; Hollywood filmmakers Rob Marshall and Antoine Fuqua; and, in sports, Curtis Martin, a National Football League Hall of Famer.

He hoped his high standards and the value he saw in each individual helped to build a shared sense of community and belonging. His hard work appeared to pay off. Before he retired in 1991, Allderdice had been named one of the seven best integrated high schools in the country.

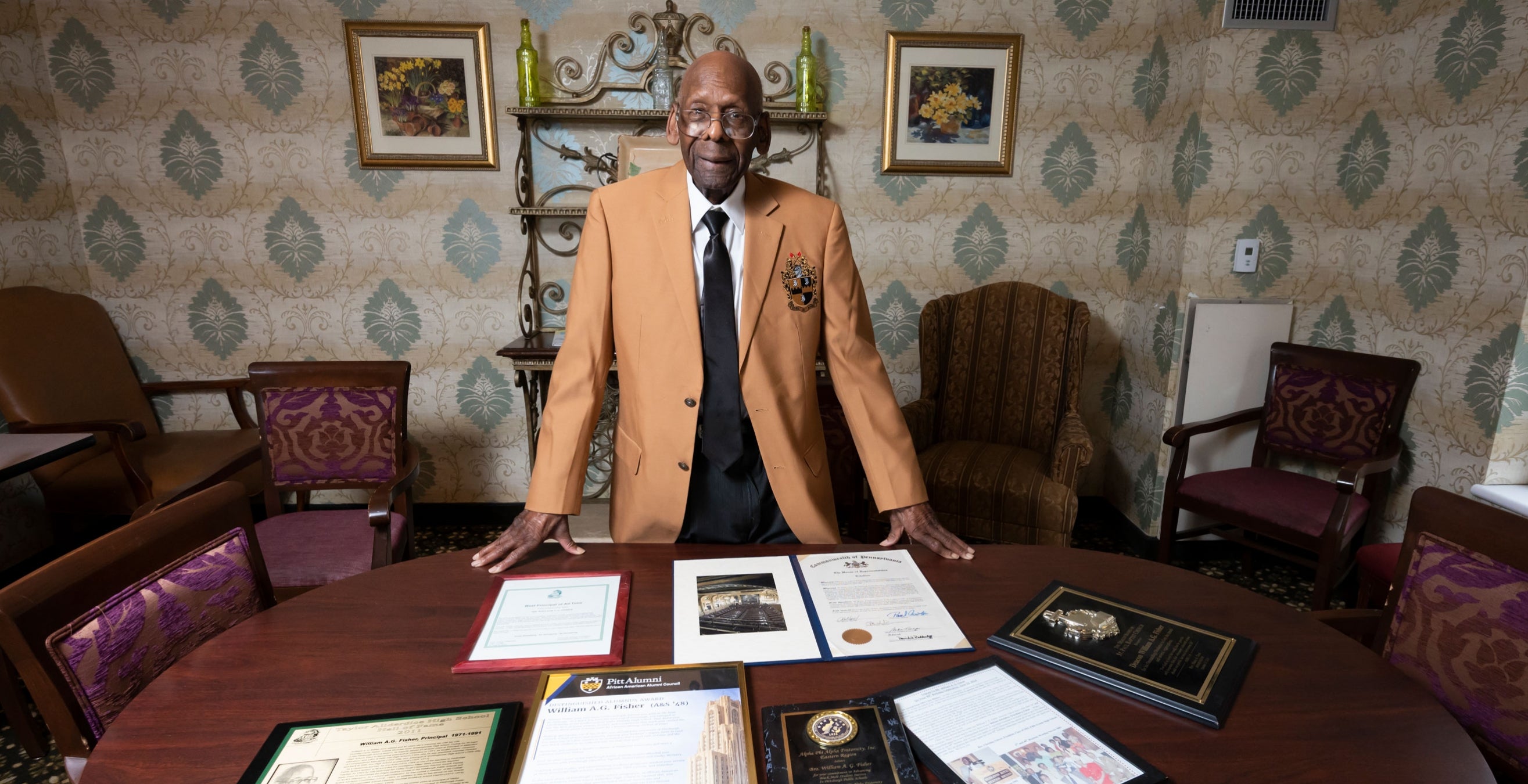

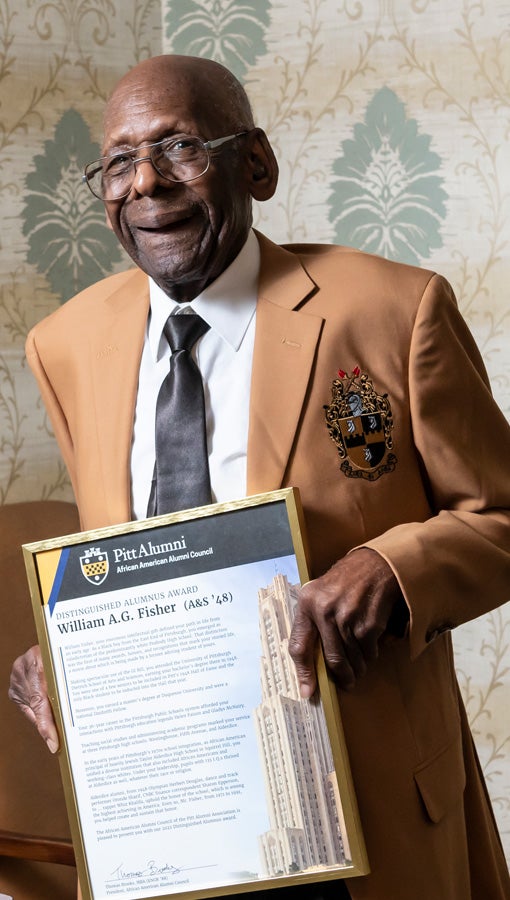

At Pitt homecoming of 2022, a year after the Divine Nine monument was unveiled, Fisher received an outstanding alumni award from the Pitt African American Alumni Council. At the celebration, many Alphas were in attendance. He had brought pride to his alma mater and his fraternity.

In looking back at all his accomplishments, Fisher can’t help but think of the joy his grandmother would have felt at the life he forged.

“I owe it all to her,” he says. “She knew the worth of education even more than I did. And that's the reason I began to reach for all that I did.”

It helped, of course, to have a supportive Pitt and Black Greek-letter community ready to take his hand and lift him toward his dreams.

This story was published on February 2, 2023. It is part of Pitt Magazine's Winter '23 issue.