The building on the outskirts of Athens, Greece, had no lights or heat at first. That didn’t stop the volunteers. There were shelves to stock with donated medicines, supplies to organize and community members to help.

Two of the founders of the grassroots pharmacy — an 83-year-old former merchant mariner and labor activist and his wife, a retired schoolteacher — were not health care professionals. But they saw an urgent need. In the wake of severe cuts in government spending, Greece faced shortages in medical personnel, medicines and supplies. At the same time, incidences of HIV/AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis were on the rise.

As the emergency grew, citizens rose up to help.

Anthropologist Heath Cabot met the couple not long after returning to Greece in the winter of 2015. After earning a prestigious Fulbright scholarship, she was starting new research on the all-volunteer social solidarity clinics and pharmacies that had emerged across the country.

Cabot interacted with the couple and hundreds of others in Greece as she evaluated how rights and entitlements changed under austerity and how people respond to such changes. She closely followed about 30 individuals to gather insights into the effectiveness of the citizens’ groups meant to assist others during the ongoing financial crisis.

Cabot interacted with the couple and hundreds of others in Greece as she evaluated how rights and entitlements changed under austerity and how people respond to such changes. She closely followed about 30 individuals to gather insights into the effectiveness of the citizens’ groups meant to assist others during the ongoing financial crisis.

She’s well suited for this people-oriented approach —t he bread and butter of cultural anthropology. Cabot’s research is fueled by critical ethnography, a qualitative research method that embraces listening to individuals and exploring how biases embedded in social systems can lead to unequal power relations. One of the paramount goals of the method is to foster social change, explains Cabot, who today is a Pitt associate professor of anthropology.

For her work, she says, “Being critical means to take a certain kind of step back and look at systems that we might easily take for granted and to understand their logic, to understand how they work. I think that’s actually very liberating, because maybe it can give societies a chance to think about how they might produce different systems.”

Her research has wider implications for understanding how traditional institutions and structures can often fail to meet people's needs, and how more organic, local and people-powered solutions arise to face key challenges—a phenomenon seen all over the world during the COVID-19 pandemic. Still, her research participants would also note the importance of not replacing those structures and institutions but challenging them to respond better.

Her career is generating recognition. She was awarded one of the 2021 Chancellor's Distinguished Research Awards. In choosing her as a Junior Scholar, Chancellor Patrick Gallagher noted that her peers consider her “one of the most active and important young voices in anthropology today.” She also received international distinction this spring by being selected to deliver the University of Oxford’s prestigious annual Elizabeth Colson Lecture.

Cabot says part of the credit for her career trajectory goes, at least indirectly, to her grandmothers. She says they instilled in her a curiosity of what it means to be human and an intellectual. As a self-proclaimed “total nerd,” Cabot took that curiosity to the University of Chicago, where she studied religion and the humanities before earning a PhD in cultural anthropology from the University of California.

For her current project in Greece, she’s built trusted sources. Also, word-of-mouth leads and fluency in the language helped open doors for her to step into the neighborhood solidarity networks— or organized groups of individuals actively helping others through relationships of mutual aid. She was welcomed into that pharmacy outside of Athens where she spent time as a volunteer, sorting medicines and immersing herself into its day-to-day operations and the lives of those it serves.

Her work probes how the solidarity structures explicitly operate outside of state, nongovernmental and corporate entities. She’s found that they not only aim to “fill gaps” in official social support systems—but as they cobble together caring spaces, they also challenge the bureaucratic systems to respond to ever-growing forms of social suffering.

“Normally when we think about redistribution,” she says, “it’s about centralized authority, how a very hierarchical system takes resources and distributes them.” And often, she notes, it’s the goal of those systems to operate as a philanthropy or charity, which often serve to “increase the status of the giver while diminishing the receiver.”

However, the goal of the social clinics is to provide services through non-hierarchical practices that emphasize equality and dignity.

When Cabot first began research in Greece in 2004, she focused on refugees. It culminated in a well-received book, “On the Doorstep of Europe: Asylum and Citizenship in Greece” (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014).

“A lot of my earlier work,” she says, “was about how refugees had to present themselves to be good victims, how to show themselves to be worthy of the protection they were, by right, supposed to already be able to access. A lot of the ways in which they had to approach the state, the health care system, the legal system were about being needy in an appropriate way.”

In her ongoing study, she’s taking a broader look at what she calls “displacement beyond place.”

“I think society focuses a lot of anxiety on movement across borders.” But what also needs to be examined, she believes, is to what extent value systems and bureaucracies are actually displacing and excluding people—in all of our communities and neighborhoods. So now, part of what she’s investigating is how people seek to provide aid without compromising an individual’s dignity or the dignity of groups of people.

She thinks the people-powered pharmacy near Athens could be a model of what’s possible. Although all of the workers in those spaces were self-organized, the pharmacies were able to assist diverse groups. In 2015 and 2016, for instance, solidarity initiatives provided crucial help to many of the more than a million refugees and migrants who entered Europe via Greece to flee war and persecution in their homelands.

There are many ways society’s systems can fail, leaving those in need without help. But Cabot says her research has demonstrated that most people, regardless of their backgrounds or careers, can participate in providing aid and building solidarity in their communities. A little unity can go a long way.

Breakthroughs in the Making

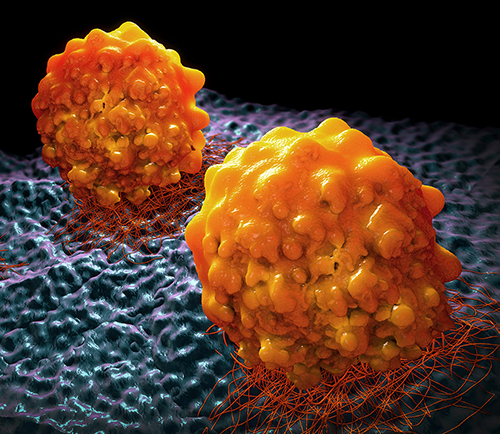

Surprising Cancer Fighter

Surprising Cancer Fighter

Fecal transplants might sound, er, strange, but a team from the UPMC Hillman Cancer Center and the National Cancer Institute has recently demonstrated that the therapy can help some patients effectively fight a certain kind of cancer. The study, published in Science, focused on people with advanced melanoma, a serious skin cancer, who had never responded to immunotherapy. Researchers already knew that the composition of gut bacteria can change the likelihood that immunotherapy will be effective. So, the team collected fecal samples from patients who responded very well to immunotherapy and transferred them via colonoscopy to the intestines of patients who had never previously responded to immunotherapy. The result: Of the 15 patients who received a fecal transplant and subsequent immunotherapy, six showed either tumor reduction or disease stabilization lasting more than a year. “Even if much work remains to be done,” said Hassane Zarour, co-senior author and professor of medicine at Pitt, “our study raises hope for microbiome-based therapies of cancers.”

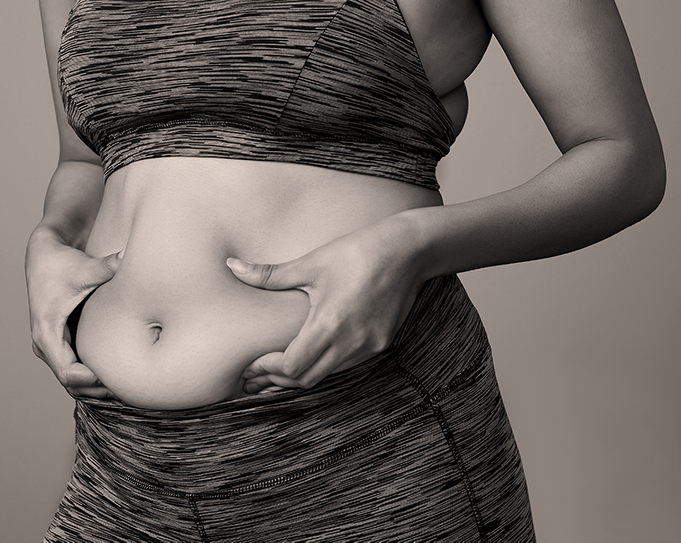

Gut Check

Gut Check

Heart disease is the leading cause of death for women in the United States, so it’s vital to know the risk factors. A recent study led by researchers at the Graduate School of Public Health has found evidence of a new one. Using 25 years of data collected on hundreds of women, senior author and associate professor of epidemiology Samar El Khoudary and her team found that women who gain abdominal fat at an accelerated pace during menopause are at greater risk of heart disease, even if their weight remains steady. “Historically, there’s been a disproportionate emphasis on BMI and cardiovascular disease,” said El Khoudary. “Through this long-running study, we’ve found a clear link between growth in abdominal fat and risk of cardiovascular disease that can be tracked with a measuring tape but could be missed by calculating BMI. If you can identify women at risk, you can help them modify their lifestyle and diet early to hopefully lower that risk.”

Parental Guidance

Parental Guidance

Children from low-income families often start school behind their classmates and struggle to catch up—a problem linked to pervasive inequity. A national study led by the University of Pittsburgh and New York University has found evidence that one solution to breaking this cycle may make quite an impact. Researchers—co-led by principal investigator Daniel Shaw, distinguished professor of psychology at Pitt and director of the Center for Parents and Children—examined the effectiveness of the Smart Beginnings Project, which promotes school readiness in low-income families by improving parent-child interactions beginning shortly after birth. The results showed large increases in parents engaging their children in reading, playing and talking—activities believed to prepare kids for success in the classroom. The study will continue to follow families over time.

This story is part of Pitt Magazine’s special Summer ’21 digital issue.