On the corner of 12th and Washington streets, not far from the railroad tracks and the rumbling smokestacks of Pittsburgh’s Edgar Thomson steel mill, a pride of teenagers gathers on the cobblestone roads, under the streetlights. It is 1955, and they rush out into the warm September night for another round of touch football. One friend brings a Jet magazine, the popular weekly that covers African American news and entertainment. What they see in the glow of twilight shuts down their frolic. Sprawled across the magazine’s pages is the story on Emmett Till, the Chicago teenager murdered during a visit to rural Mississippi for the claim of whistling at a White woman.

Under the lights, Curtiss Porter stares at images of Till’s bloated, battered body. He and his friends had heard of Till, the brutality of how he was killed had ripped across the nation, and, this evening, through their youthful innocence. Although the murder took place in what Porter considers the distant South, some 800 miles from his home in a Pittsburgh suburb, Braddock, the 15-year-old is now disturbingly aware of the threat of racial division.

It was a “huge wake-up call,” recalls Porter. “We were the same age as Emmett and felt like we were in relationship with him. If it could happen to him, it could happen to us.”

On that corner, Porter has what he calls a “moment of righteous indignation.” A moral clarity roots itself into his soul, calling him to become a champion for inclusion. About a decade later, and in the thrust of the modern civil rights movement, Porter makes his way to the University of Pittsburgh. He would soon have to face his calling.

Fifty-seven years later, another teenager slips out into the dark, cold morning of Feb. 27, 2012. Edenis Augustin lives in Rockland, N.Y., and the middle-school student is headed for the bus stop. He has on his blue sweater, the one with the hoodie. He’s got his swag on. It’s his 14th birthday. As he boards the bus, his friend, in distress, asks him, “Did you hear?”

Fifty-seven years later, another teenager slips out into the dark, cold morning of Feb. 27, 2012. Edenis Augustin lives in Rockland, N.Y., and the middle-school student is headed for the bus stop. He has on his blue sweater, the one with the hoodie. He’s got his swag on. It’s his 14th birthday. As he boards the bus, his friend, in distress, asks him, “Did you hear?”

“No,” Augustin replies.

His friend fills him in: An unarmed Black teenager, Trayvon Martin, was shot dead the night before while returning from the store in Florida when a White neighbor allegedly mistook him for a trespasser. He was carrying Arizona juice cocktail. Just like me, says Augustin. He had a bag of Skittles. I like Skittles, says Augustin. And, he was wearing a hoodie. Just like me, says Augustin.

In the 10-minute ride to school, Twitter blew up, recalls Augustin. “Everyone was asking, how could this happen? It could have been me. He was two years older than me. I would wear my hoodie all the time. I feel like it could have happened to me at any time, anywhere.”

Augustin is growing up. Just like Porter’s boyish innocence was shattered 57 years ago, so is Augustin’s, as he, too, now has to face the horror of racial violence. “I remember thinking,” says Augustin, “this is America right now. But is this how it’s going to be for the rest of my life?”

Porter and Augustin come from two different generations, but parallel experiences have led each—in his own time—to the University of Pittsburgh. Each to leadership with the Black Action Society. Each to stand together in solidarity to the causes of inclusion and equality.

In mid-January, each is among the standing-room-only crowd packed into the Kurtzman Room at Pitt’s Student Union to commemorate the founding of the University’s Black Action Society and, in particular, a dramatic turn of events 50 years ago that transformed the campus and community.

A half-century ago, Porter (A&S ’69, EDUC ’84G) was a central strategist in what came to be called the Computer Center Takeover. It happened on Jan. 15, 1969, the day Martin Luther King Jr. would have been celebrating his 40th birthday had he not been assassinated the previous year, April 4, 1968. What better way to honor King’s memory, believed Porter and his BAS colleagues, than to confront what they considered a slow University response to calls for inclusion.

In the evening, the students marched to the Cathedral of Learning’s eighth floor and locked themselves in the Computer Center, which at the time was a central repository of financial, academic, and student records. To shut it down was one way to get the administration’s attention.

In the evening, the students marched to the Cathedral of Learning’s eighth floor and locked themselves in the Computer Center, which at the time was a central repository of financial, academic, and student records. To shut it down was one way to get the administration’s attention.

But it was risky. There had been violence at other colleges with similar confrontations. The students faced losing their scholarships, being expelled, or imprisoned.

It was a “brave action that led to significant progress,” says University Provost Ann Cudd, who quickly adds that “there is so much more to do to improve the diversity and inclusiveness of our campus community.”

After hours of cordial negotiations, early the next morning, the sit-in ended. Porter and his classmates weren’t disciplined. Instead, their direct action helped open wide the doors for greater recognition of the Black experience at Pitt. It created a Department of Africana Studies (formerly Black Studies), increased the Black student body, and recruited African American professors and administrators who continue to attract national and international distinction. It created a Black alumni network of more than 20,000 who continue to achieve and contribute to Pitt’s story.

Among the alumni is Bennet Omalu, who was first to discover and publish findings of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) in football players. Then there is three-time New York Times best-selling author and writer Bebe Moore Campbell, and poet Terrance Hayes, who in 2014 received the MacArthur Fellowship for outstanding creativity.

The list of accomplished Black alumni goes on and on.

Perhaps that list would not be what it is had it not been for Porter, a curious, young man who wore a modified Afro when he enrolled in 1966. Two years later he joined with like-minded students and community members to create the Black Action Society the same evening that King, the civil rights leader, was slain.

But before King was murdered and before Porter walked onto campus, much of his sense of community and reaching for change had taken shape in nearby Braddock, the once-thriving mill community where Porter was born. Growing up there, he was surrounded by immigrant Europeans who came to work at the mills and make a new life. It was the same for his parents, migrants from the American South, who came to escape Jim Crow segregation and find new opportunity.

They settled in The Bottom, a nearly all-Black area closest to the dust and pollution from the mills. White folks lived farther away, up on the hill. Porter’s father worked in the Edgar Thomson factory, and his mom ran a small eatery, selling food and drink from their home.

Although neither parent had the opportunity to advance beyond third grade, they valued education and raised their sons and daughter accordingly. The family owned a set of encyclopedias, and the children would sit in the middle of the dining room absorbing the reports, fables, rhymes, and riddles throughout the night. Porter was exceptionally inquisitive, about himself, about society. He read at an early age and often found himself in the local library, his imagination lost in the stories of King Arthur.

By the time Porter is a teenager, events in Braddock and beyond push him to question race relations. First there is the gut-wrenching murder of Till. But he also notices that in high school, classes that were once integrated are now segregated. Around the same time, Porter, an honors student, begins to hang out with troublemakers. Subsequently, his grades lag, so when he graduates, his best option is to enlist in the U.S. Air Force.

It is the era of the Vietnam War, and Porter says his “first overseas assignment was Mississippi.” He was sent to Biloxi, where the stark segregation off base was suffocating. Airmen who could be friendly on base weren’t allowed to eat together or even walk together when they ventured into town. The glaring racial inequality was another rude awakening for Porter.

Augustin isn’t even born when the Pitt students take over the Computer Center. In fact, his parents aren’t even in this country. Immigrants from Haiti, they moved to the United States in 1999, when their first-born child, Edenis, was 2.

Augustin isn’t even born when the Pitt students take over the Computer Center. In fact, his parents aren’t even in this country. Immigrants from Haiti, they moved to the United States in 1999, when their first-born child, Edenis, was 2.

The family settled into a village in Rockland, N.Y., full of Haitian culture and pride. His cousins and aunt lived there; Haitian Creole was spoken in the churches; a Haitian flag celebration happened every year. In Haiti, his father, Emmanuel Augustin, worked as a teacher and guidance counselor. In Rockland, he worked as a janitor. He taught his children that a good education could give them unlimited possibilities. When they were young, Pops sat with his children at a little yellow table and taught math and writing.

Life in Rockland was quiet. Outside of the village, two things happened that would shape how Augustin saw the promise and peril of being Black in America. First, when he was in fifth grade, the glare of the Obama presidency forced him to observe life beyond his ethnic enclave. Obama inspired Augustin. He stayed up all night to watch the election results of 2008. He was awed by the progressive political outsider who opened up Augustin to consider how one didn’t have to be confined by issues of class, identity, and race. Obama was African and American. Augustin was Haitian and American.

But then, about four years later, short into Obama’s second term, teenager Trayvon Martin was senselessly killed in Florida. Not too long afterward came the incomprehensible deaths by police of Eric Garner, 43 (killed in a chokehold while under arrest in New York for selling cigarettes); Michael Brown, 18 (shot in an altercation with an officer in Missouri); and Tamir Rice, 12 (shot dead while playing in a Cleveland park). With each death, Augustin became more and more defiant.

“I still wore my hoodie. My mom was antsy about it, but I didn’t want circumstances to limit me.” He also grew more conscious of the biased narrative surrounding Black males—it seemed that their deaths were somehow justified because they were stereotyped as gang members or thugs.

Augustin wouldn’t let himself be stereotyped. He pushed himself. He didn’t just play football. He was an accomplished cornerback and was captain of the team. He wasn’t just a good student; he belonged to every honor society at Spring Valley High and graduated as valedictorian. “If I was murdered,” he says, “I did not want to give anyone reason to think that ‘he’s guilty’ and that it was something I deserved or brought on myself.”

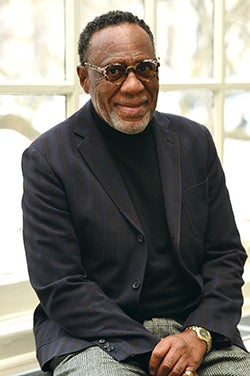

Porter is a high achiever, too. He went on to have a career as a university chancellor and as an executive with the City of Pittsburgh. But in the fall of 1966, when he first comes to Pitt, he’s a sinewy 26-year-old accountant, dreaming of becoming a writer.

The former airman chose Pitt partially for its affordability and acceptance of credits from his previous college. He is open to new experiences, but settling in at Pitt is difficult. He recalls that only one half of 1 percent of the student body was African American. As Porter puts it, “the Whiteness was overwhelming.”

He is often the only Black student in his classes. Like many of his Black colleagues, he feels invisible on campus. They lack Black faculty mentors and feel that courses largely ignore their culture and history.

But in 1966, King comes to campus with his message of love and integration. The next year, the charismatic Black Power advocate Stokely Carmichael comes with his philosophies of organizing for survival and progressive development. The visits, particularly Carmichael’s, leaves the Black students abuzz and not knowing what to do next.

As Porter witnesses the confusion, his military experience kicks in, and he steps up to help organize.

As Porter witnesses the confusion, his military experience kicks in, and he steps up to help organize.

“I never saw myself as a leader. I was primarily someone who observed society, analyzing, puzzling over why things worked the way they did. But I put my voice in,” he says. “I had a moral outlook.”

On the 1960s campus, Porter is often adorned in a brown, worn-leather jacket. He takes the West African name of Okigpo. Like other BAS members, and the larger society, he is inspired by the nonviolent philosophy of King and the Black Power advocacy of Carmichael. Embracing the duality, they foster the African American Cultural Society, a precursor to what would become the Black Action Society.

About a year later, the evening of April 4, 1968, the Black Action Society is created in response to the assassination of King. Its Student Union office, painted black, becomes a safe space. At the time, says Porter, Black is a broad identity, but it’s not “monochrome,” and the BAS unifies Black American athletes, fraternity and sorority members, African classmates, and rural and urban students.

Across their differences, as students coalesce in energy and spirit, they push the University administration on key, progressive demands—the recruitment of more Black students, faculty, and staff; the establishment of a Black Studies program; and the creation of more Black-centered campus programming. After months of pressing, on Jan. 15, 1969, the birthday of King, and just nine months after the BAS began, the students take action. They take over the Computer Center. And the changes they wanted would soon begin.

In the fall of 2016, Augustin, who had his choice of top colleges, comes to Pitt, in part because of the inclusive foundation Porter helped start. But before the semester is over, America has elected a new president.

Times are changing. They are different on campus, too.

About a year before Augustin arrives, Pitt created its Office of Diversity and Inclusion, to partner with organizations such as BAS and others to make the campus community more welcoming.

Today, about 5 percent of Pitt undergraduates identify as Black or African American. Although, like Porter, he’s sometimes the only African American or Haitian American in his classes, Augustin feels accepted.

New identities have changed campus, too. The Black Action Society, while open to all students and once the umbrella organization for Black diversity, now stands side by side with at least a half-dozen other groups that push for inclusion for people of color.

Augustin, who was a busy, active student in high school, thought he’d come to campus and focus on his studies. He wants to be a psychologist. Early on, he accepted an internship with the BAS. He was not looking for leadership, just belonging. But his levels of responsibility with the group kept expanding.

In the years since, Augustin, as president, has participated in programming—such as the Black Prestige Gala—to draw the diverse groups and agendas together, feeling that one strengthens the other. He has had to negotiate intersectionality, the understanding that the groups don’t just fit into one category: Being Black intersects with LGBTQ, gender, class, and other issues.

In the years since, Augustin, as president, has participated in programming—such as the Black Prestige Gala—to draw the diverse groups and agendas together, feeling that one strengthens the other. He has had to negotiate intersectionality, the understanding that the groups don’t just fit into one category: Being Black intersects with LGBTQ, gender, class, and other issues.

“Intersectionality,” he says, “provides a wider scope to work with. You can’t just turn a blind eye to who people are. With everything that’s going on, we have to fight more than individual goals. We have to fight for other people.”

The January commemoration of the BAS 50th anniversary signifies the continued importance of diversity and inclusion as values that propels positive change for all at Pitt. When it is over, celebrants march out behind African drummers and a young woman singing a freedom chant.

Fifty of the marchers carry lamps, representing the long history of the light of pride and progress. Augustin is near the front, leading the contingent, holding his lamp high. Porter is not far behind. He is watching the young man take the same steps from the Student Union to the Cathedral that students took 50 years ago to launch the sit-in. He smiles in the glow. The light is moving onward.

Read more about the Black Action Society's earliest members here.

Opening image from the commemoration of the Black Action Society's 50th anniversary.

This story appeared in the Spring 2019 edition of Pitt Magazine.